Western Americana refers to a stylistic and cultural movement rooted in American heritage. It draws its references from the imagery of the Western Frontier, cowboy folklore, American-made workwear, and even military elements. It is a timeless and rugged style, built on iconic garments deeply embedded in the history and collective memory of the United States. Its origins date back to the 19th century: during this era of westward expansion and industrialization, cowboys, railroad workers, farmers, and American pioneers unknowingly laid the foundations of the Western Americana aesthetic by adopting utilitarian outfits designed to withstand the harsh conditions of the terrain.

Over time, these functional garments transcended their original purpose to become true cultural symbols. From riveted jeans to leather boots, including the Stetson hat and the denim jacket, each piece tells a chapter of the American frontier mythology. Starting at the turn of the 20th century, the popularity of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows, followed by Hollywood westerns, brought these clothing codes into the mainstream. Western Americana thus evolved from utilitarian dress to a fully fledged aesthetic, conveying values of authenticity, freedom, and nostalgia for the Wild West. Before diving into its various facets, let’s clearly define what makes up this unique style and how it came to be.

The term Western Americana describes a style inspired by American cultural heritage, particularly that of the North American West. It’s a true melting pot of influences, blending the ruggedness of workwear, the legendary allure of cowboys, the contribution of military surplus, and pioneer folklore. In practice, this style is characterized by simple, durable garments weathered by time, closely tied to the iconography of the American nation. Think of the snap-button western shirt, the denim jacket, the red bandana, heavy canvas trousers, or cowboy boots—retro pieces inseparable from the imagery of the Wild West.

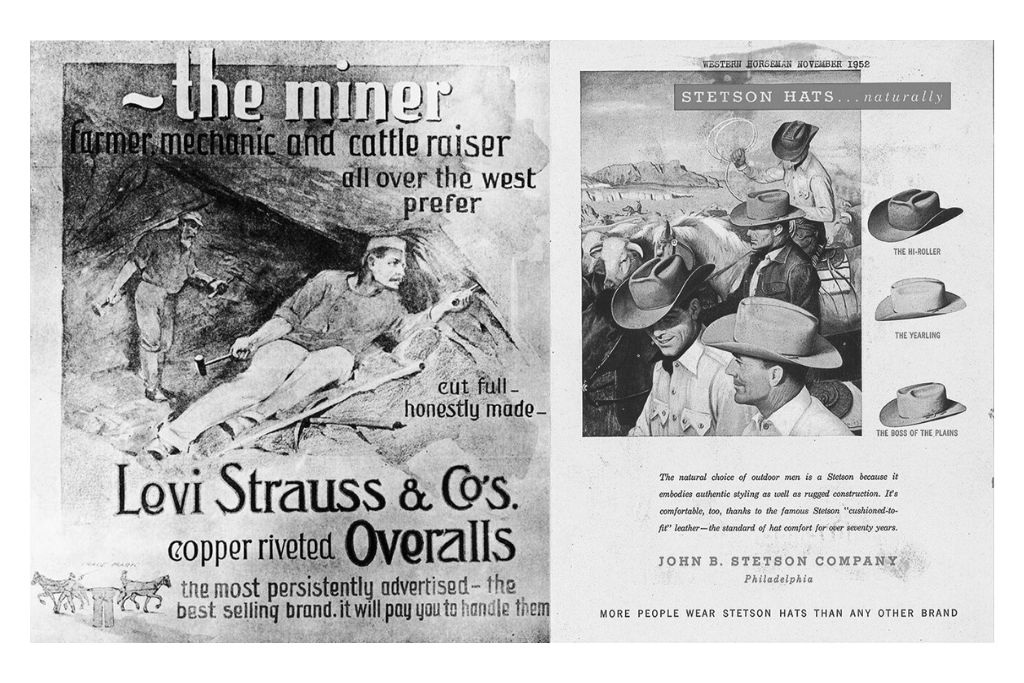

Historically, the Western Americana aesthetic takes root in the second half of the 19th century. At that time, the young American nation was shaped by westward expansion, the Gold Rush, and major railroad construction. Iconic garments emerged out of necessity. In 1853, in San Francisco, a man named Levi Strauss began supplying miners with heavy-duty work pants dyed with indigo—the future denim.

Worn loose and held up by suspenders, these pants were an immediate success, as they held up far better than regular clothing under the harsh conditions of mining work. In 1873, Levi Strauss partnered with tailor Jacob Davis to patent the revolutionary idea of adding copper rivets to pocket stress points, preventing them from tearing under the weight of tools. This marked the birth of the riveted blue jean, which would leave a lasting impact on workers’ clothing and eventually become a symbol of modern America.

At the same time, other clothing innovations marked this period. Cowboys and plains ranchers adopted specific boots with pointed toes and angled heels, ideal for the stirrup—designs inspired both by Mexican vaquero boots and European models. In 1865, hatmaker John B. Stetson created his wide-brimmed felt hat, drawing on the idea of the Mexican sombrero, to protect workers from the scorching Texas sun. Flannel plaid shirts, leather fringe jackets worn by trappers, and cotton bandanas used to shield from dust were also part of the 19th-century Frontier landscape. Originally purely functional, all of these items now form the authentic foundation of the Western Americana style.

It’s important to emphasize that Western Americana was built by borrowing from many cultures. As curator Brenda Colladay explains, “Western wear is a true melting pot of influences: designs and materials of Native Americans (suede, beads), costumes from Buffalo Bill’s shows, utilitarian denim, uniforms of Mexican vaqueros and cowboys, folk motifs brought by immigrants… all fused into the Western style.”

Indeed, Hispanic heritage (from Californian vaqueros to Texan rancheros), Native American traditions (dyeing, weaving, turquoise ornamentation), and the contributions of European settlers each enriched the fashion of the American West over several decades. The result is a hybrid style—halfway between utilitarian pragmatism and cultural ornamentation—that embodies the myth of pioneer America.

With the 20th century, this aesthetic moved beyond the rural West to infuse American popular culture as a whole.Hollywood films from the 1930s to the 1950s elevated the cowboy look to iconic status (more on that later), while workwear and military garments gradually entered civilian wardrobes across the country.

Western Americana then became a cross-class and intergenerational style: worn by workers and rockstars alike, by rebellious hippies or fashion designers. We will now examine the main stylistic currents that make up this aesthetic—each one a world of its own, tied to a particular chapter of American history.

The Americana style is not monolithic—it is a universe with many facets. It was built by aggregating various American fashion currents—some very old, others more recent—that together form its identity. Several major categories can be identified: the classic cowboy style inherited from the Frontier, the workwear wardrobe of American laborers, the influence of 20th-century military surplus, the legacy of American motorsports, and the contributions of rock ’n’ roll and Ivy League collegiate style. Each of these currents has its own codes, signature pieces, and historical narrative, but all converge into what is now called Western Americana.

The following sections break down each of the main stylistic currents that make up the Western Americana aesthetic. To explore further, each theme is the subject of an in-depth article accessible via the title link.

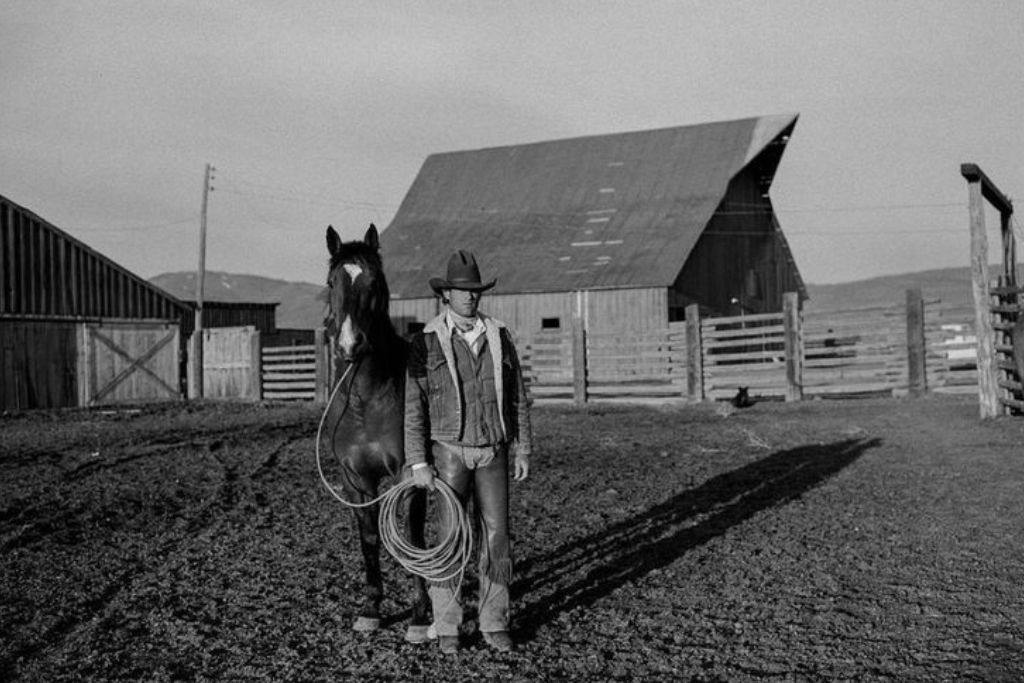

Cowboy history and its style are arguably the soul of Western Americana, as the figure of the cowboy holds a mythical place in the American imagination. Emerging in the second half of the 19th century, the cowboy of the West—often a young cattle herder or rider guiding livestock across the plains—developed a specific attire, shaped by the demands of the job and a certain sense of flair.

A classic cowboy outfit includes a wide-brimmed hat (often a Stetson), a sturdy shirt (cotton or flannel) worn under a vest or leather jacket, a bandana tied around the neck to protect from dust, jeans or heavy canvas pants tucked into leather boots with spurs, and sometimes leather chaps for horseback riding. Each item had a practical function originally—whether the hat’s shape for sun protection or the boot’s heel for stability in the saddle. But very quickly, the ensemble took on a powerful symbolic dimension: that of the free man, resilient, one with the wild nature around him.

As early as the 1880s, cowboy imagery spread widely throughout the United States and internationally, thanks to Buffalo Bill’s traveling shows. Characters like Buffalo Bill Cody himself or sharpshooter Annie Oakley, through their Wild West Shows, brought the western silhouette to the general public. With a Stetson perched on their heads, fringe jackets, and boots on their feet, these theatrical “heroes of the West” established the visual codes of the cowboy in the collective imagination.

In the 20th century, Hollywood took over: actor John Wayne, in his countless westerns starting in the 1930s, embodied the ideal, archetypal cowboy for decades. His uniform—hat, sleeveless leather vest, oversized belt buckle, and silk scarf—became inseparable from the cowboy on screen and influenced generations of viewers. At the same time, feminine iconography of the Wild West also emerged, with figures like Marilyn Monroe or Jane Russell posing as glamorous cowgirls in the 1940s–50s.

Even today, cowboy style remains a key component of Americana fashion. Its iconic pieces—western boots, concha-studded belts, plaid shirts, or shirts with signature yoke panels—are reinterpreted season after season by designers.

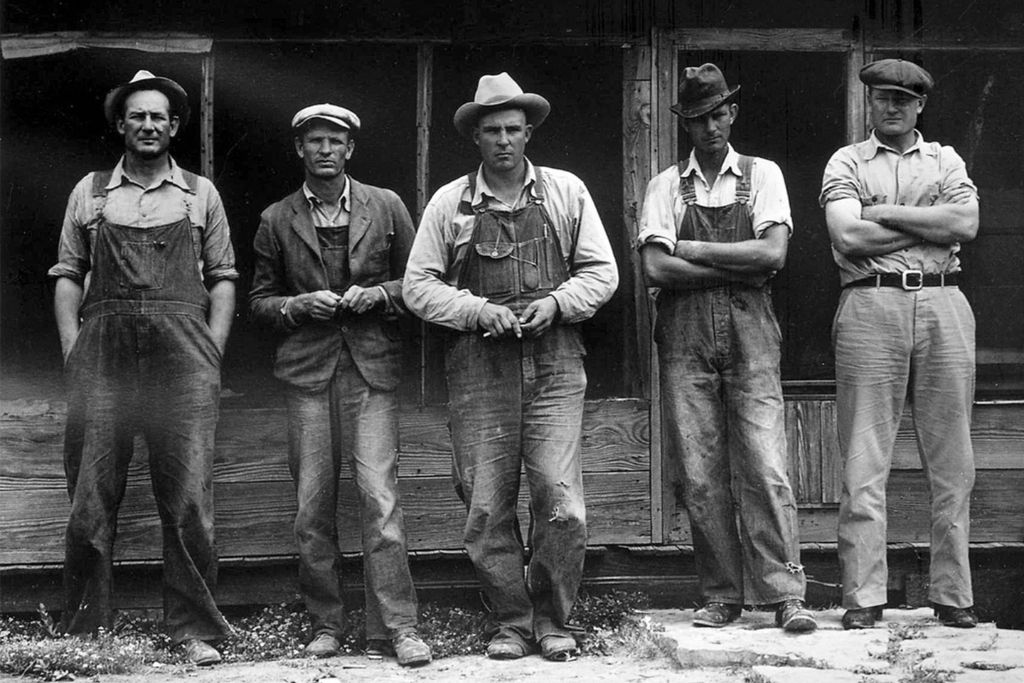

The Americana Workwear current refers to the entire blue-collar work wardrobe of the United States—that is, clothing originally designed for American manual laborers. Americana Workwear, or the style of American work clothing, subtly tells the story of the country’s industrial and social epic. Designed first and foremost to be functional—durable, practical, and comfortable—these utilitarian outfits gradually rose to the status of iconic “American uniform.”

They evoke the conquest of the West, the building of the railroads, construction sites, farms, and the ideal of hard work. Visually, this style is recognizable by its use of tough materials (heavy denim, canvas, tanned leather, cotton flannel), simple and roomy cuts allowing freedom of movement, and functional details (utility pockets, reinforcement rivets, sturdy topstitching).

In the young 19th-century America, gold prospectors, laborers, farmers, and cowboys needed garments capable of withstanding grueling daily life. It’s from this vital need that workwear fashion was born.

As previously mentioned, Levi Strauss laid the foundation for jeans in 1853 by supplying miners with durable pants, then revolutionized the genre in 1873 with the introduction of copper rivets on blue jeans. These riveted work jeans, initially worn wide and high-waisted with suspenders, became the ultimate reference for tough trousers. Soon after, other entrepreneurs followed suit: in Detroit in 1889, Hamilton Carhartt founded his manufacturing company and introduced overalls and jackets specifically designed for railroad workers and industrial laborers.

His motto—offering “honest value for an honest dollar”—translated into the use of ultra-thick cotton fabrics (heavy denim or treated duck canvas) capable of enduring the harsh conditions of rail construction and factory work. Other pioneers like Dickies (founded in 1922 in Texas) followed his lead, producing robust work garments to equip laborers across the country.

Alongside the mines and factories, workwear also drew on rural traditions. Western farmers and ranchers, with limited means, often made their own work garments using locally available materials—mainly leather from their own livestock, which they turned into jackets, aprons, and sturdy gloves. These rural pieces prioritized durability and thriftiness, even if the result appeared rustic. By the turn of the 20th century, the American worker’s uniform was well established: denim or heavy canvas overalls, chore coat, thick shirt, high boots or sturdy brogues, sometimes topped with a work cap or knit beanie.

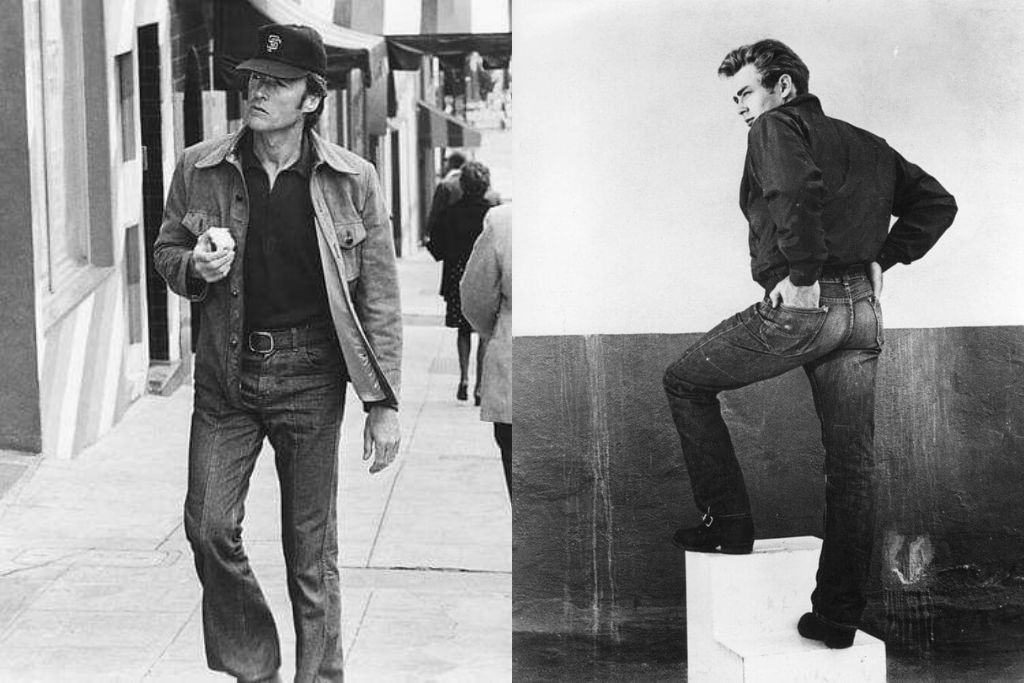

Although workwear was initially confined strictly to the labor world, it experienced a surprising second life in the 20th century—as a fashion movement in its own right. As early as the 1940s–50s, youth figures like James Dean elevated raw denim jeans and white T-shirts (originally work uniforms) to the status of rebellious youth fashion. Later, in the 1990s, popular rappers adopted Carhartt or Dickies jackets for their stripped-down, authentic look.

This street appropriation—which we’ll revisit in the Rock’n’Roll section—shows just how much American workwear has acquired an aura of authenticity and cool. Today, rediscovering Americana Workwear helps us understand why these sweat-born garments became a true fashion movement and a major source of inspiration for an entire generation of designers.

Another major pillar of the Western Americana style comes from military heritage—specifically, from the repurposing of military surplus in civilian fashion throughout the 20th century. After each major conflict—from the two World Wars to the Vietnam War—the United States found itself with vast stocks of uniforms and military gear. These rugged items, designed for the field, gradually infiltrated the everyday wardrobe of Americans, first out of practicality, then as a style statement.

The decisive turning point came in the post–World War II era. Millions of young veterans returned to civilian life, and thanks to the G.I. Bill, many enrolled in college during the late 1940s and early 1950s. On campus, it became common to see student-veterans wearing their old military garments in daily life: khaki fatigues, combat jackets, army boots… This phenomenon played a major role in the informalization of postwar American style.

Surplus stores sprang up across the country, offering military shirts, cargo pants, canvas jackets at low prices—items that appealed to students for their durability and practicality. In university outdoor and mountaineering clubs, these tough military clothes were also adopted, laying the groundwork for what would become the American outdoor fashion movement. Within a few years, the military wardrobe had embedded itself into U.S. clothing culture, to the point that some pieces became true casual classics—think of the khaki chino pants derived from uniforms, or the field jacket that would later be worn by millions of young people.

In the 1960s, the relationship to military clothing evolved further: during the Vietnam War, military surplus was co-opted by protest movements. Young pacifists and hippies wore the M-65 field jacket and khaki parka as anti-militarist symbols, flipping the original use of these garments into tools of protest. Wearing an old U.S. Army jacket became an act of defiance—a rebellion against the establishment—especially when decorated with peace and love patches.

Like jeans and bandanas, military thrifted garments became part of the American protester’s uniform around 1968. This subculture helped detach these clothes from their military connotation and anchor them permanently in civilian fashion. Later, in the 1970s and ’80s, camouflage patterns and U.S. Air Force bomber jackets would even see a resurgence in popularity among certain urban subcultures.

Today, the military surplus influence lives on through key pieces often found in Western Americana outfits. The M-65 field jacket (introduced in 1965 during the Vietnam War) is one such example: with its olive drab canvas and removable liner, it embodies both the toughness of the battlefield and the countercultural spirit of the ’70s. The MA-1 nylon bomber jacket, popularized by fighter pilots and later adopted by punk youth, is another classic.

We can also mention the OG-107 fatigue shirt, cargo pants, black combat boots, or the standard-issue GI white T-shirt—all of which have made the leap from soldier’s gear to civilian vintage staples. Their presence in a Western Americana outfit adds a layer of authenticity and historical gravitas.

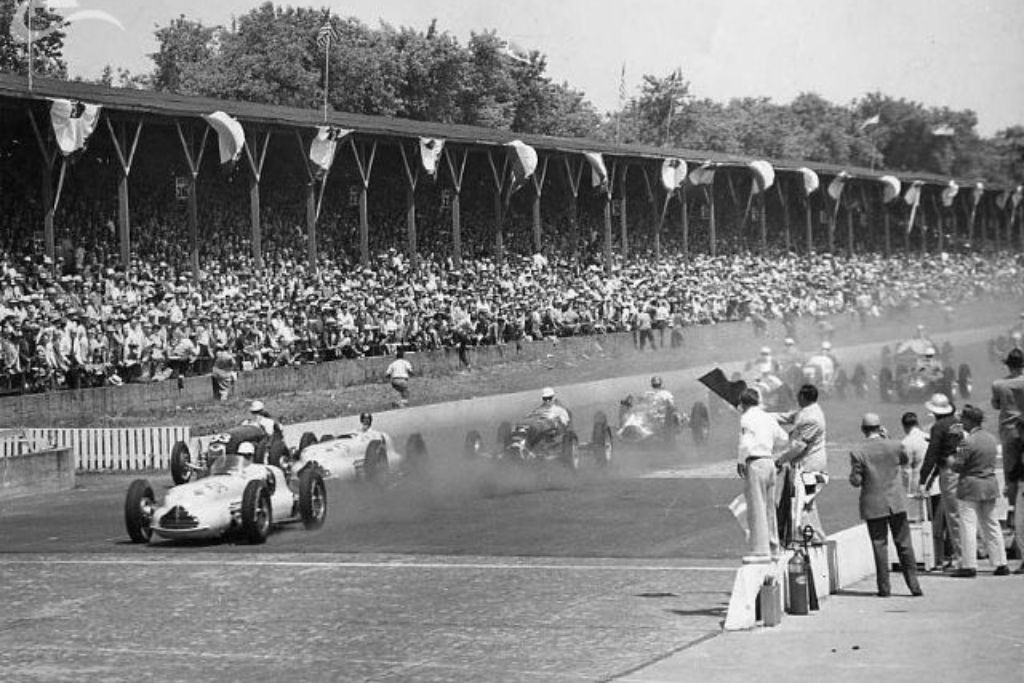

Western Americana isn’t limited to cowboy culture or rural workwear—it also encompasses the world of American motorsports, whether it be motorcycle bikers or auto racing enthusiasts. Speed, roaring engines, and the open road have been part of the great American dream since the early 20th century, and they have produced their own dress codes, which in turn have infused the Americana aesthetic.

On the motorcycle side, the figure of the American biker rose to prominence after World War II, notably with the emergence of motorcycle clubs like the Hells Angels, founded in the 1940s and ’50s.

The iconic biker style—black leather Perfecto jacket, worn jeans, engineer boots—entered legend thanks to cinema. The unforgettable image is Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953): leather cap on his head, black Schott Perfecto jacket, jeans, and boots—Brando embodied the motorcycle rebel. From that point on, the black leather jacket became synonymous with the bad boy and the freedom of the road.

This rebellious biker silhouette—white T-shirt under a Perfecto, denim, and boots—would inspire generations of youth and blend with the rock’n’roll aesthetic. The Perfecto, created in 1928 for motorcyclists, owes much of its global fame to American bikers and Hollywood: it is now a staple of counterculture fashion across the world.

Auto racing also produced dress codes that later migrated into street fashion. In the U.S., the rise of stock car racing and NASCAR (founded in 1948) popularized a distinctive style starting in the 1950s: flashy driver jackets, racing team caps, sponsor patches. In the 1990s, this imagery was recycled by urban fashion. It's striking how the NASCAR driver jacket, adorned with sponsor logos (Goodwrench, DuPont, M&M’s, etc.), became hugely trendy in hip-hop and streetwear during that time.

Artists like Tupac Shakur appeared wearing multicolored NASCAR jackets, turning a trackside garment into a fashion statement. From then on, wearing a racing team jacket or a vintage T-shirt featuring a racing legend was more about style than mechanical passion: in the ’90s, people proudly wore Dale Earnhardt gear without necessarily following the races. Even high-end designers embraced the trend in the 2010s, like New York brand Aimé Leon Dore, which restored vintage Porsches and created an entire collection inspired by the racing aesthetic of the ’60s–’70s (quilted driver jackets, leather gloves, etc.).

Ultimately, the motorsport legacy in Western Americana is expressed through a few standout pieces: the leather biker jacket (whether minimal or adorned with club patches and emblems), vintage racing-printed motocross jerseys, knotted bandanas (as worn by bikers and drivers), reinforced motorcycle boots, sponsor-branded trucker caps, or graphic tees featuring legendary races. These elements add an industrial edge and rebellious spirit to the more traditional Americana aesthetic. They serve as a reminder that the freedom so central to this style is also expressed through roaring engines and the conquest of the open road—another kind of American frontier.

Finally, two other major influences must be mentioned—though very different from one another, both have helped shape Americana fashion throughout the 20th century: on one hand, Rock’n’Roll aesthetics, and on the other, the Ivy League style of East Coast university campuses. These two worlds—one rebellious and popular, the other elitist and preppy—embody two distinct facets of postwar American culture, and their dress codes have been partially absorbed into the broader Western Americana current.

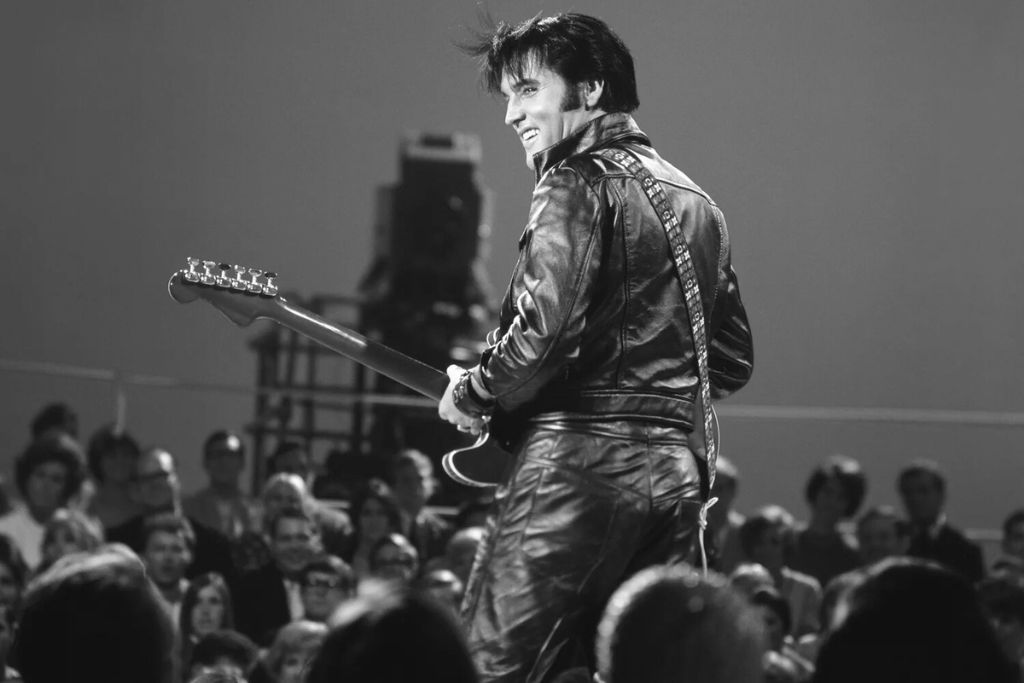

From the 1950s onward, the rock revolution transformed youth fashion and heavily drew from the Americana wardrobe.

Figures like James Dean and Marlon Brando (mentioned earlier) established raw denim jeans, the white T-shirt, and the leather jacket as the new uniform of rebels. James Dean, often photographed in Levi’s 501s and a simple tee, embodied that mix of working-class simplicity and laid-back attitude that defined cool.

At the same time, young Elvis Presley fused several influences: in everyday life, Elvis wore jeans, plaid shirts, and leather jackets like any young American of his era, but on stage, he also embraced western outfits (he played a cowboy in the film Flaming Star in 1960) and flamboyant country suits inspired by rhinestone-studded Nudie suits. With his boots, embellished jackets, and scarves, Elvis introduced rockabilly aesthetics—a blend of rock and country—into mainstream pop culture.

In the 1960s–70s, the hippie and folk movements continued this legacy: musicians like Neil Young proudly wore flannel shirts and fringe trapper jackets, Jimi Hendrix took the stage at Woodstock in a British military parade jacket paired with suede fringe trousers, while Johnny Cash cultivated his “man in black” persona in a sober, dark western outfit.

Each of these artists, in their own way, incorporated elements of American heritage clothing—be it military uniforms, farmer garments, or cowboy gear—to claim authenticity and rebellion. The message was clear: wearing worn Levi’s, a military jacket, or a fringed western coat was a way to reconnect with the people’s authenticity and, at times, defy the established order.

Rock thus permanently anchored certain Americana pieces as symbols of dissent—think of the Perfecto jacket embraced by punks, the lumberjack flannel shirts of grunge (Kurt Cobain popularized the red-and-black plaid shirt of the brooding lumberjack in the ’90s), or the bandana tied across the forehead like Bruce Springsteen or Tupac Shakur. In fact, Bruce Springsteen himself, nicknamed The Boss, embodied an ideal Americana style in the 1970s–80s: faded jeans, white T-shirt or tank top, work shirt, all paired with a folk guitar. On the cover of Born in the U.S.A. (1984), his Levi’s jeans and American flag-colored bandana tucked in the back pocket offer an iconic image of proud, working-class nostalgia.

On the opposite end of the spectrum from rock, Ivy League style refers to the traditional dress of students from prestigious Northeastern universities (Harvard, Yale, Princeton…). Popularized in the 1920s–30s and becoming a national fashion phenomenon in the 1950s, the Ivy League look—the forerunner of preppy style—consists of more formal, understated clothing: tweed jackets or navy blazers, button-down oxford shirts, club ties, wool sweaters (often in school colors), chino pants or gray flannel trousers, penny loafers and other derby shoes.

At first glance, this upscale world seems far removed from the Wild West… Yet, it is undeniably part of the Americana mosaic.For one, because it is deeply embedded in 20th-century American culture—it is the other uniform, that of the white upper-middle class of the time. And second, because vintage preppy style has also been reinterpreted and integrated into the Americana trend when paired with more rustic elements. As one observer noted, “Everything from cowboy boots … to a 1960s Ivy League pull-over can be Americana”—in other words, from cowboy boots to a vintage Ivy League sweatshirt, everything can fall under the Americana umbrella. It’s especially the retro, nostalgic dimension that allows Ivy style to merge with western or workwear pieces.

For example, an authentic 1960s Harvard university sweatshirt worn with faded Levi’s jeans and Native American moccasins makes for a highly convincing Americana look. Whereas the same Ivy League outfit in its modern version (new sweater + chinos + new loafers) would evoke a privileged youth, using vintage or timeworn pieces transforms it into an evocation of old America.

This stylistic trick—mixing vintage preppy with workwear—was popularized by brands and designers in the 2010s, riding the heritage fashion wave. Think Ralph Lauren, who often paired tweed jackets with jeans in his campaigns, or Japanese labels obsessed with old American Ivy style. GQ magazine noted that in 2008, a neo-preppy wave swept in, bringing campus style closer to workwear in a nostalgic Americana spirit.

Ultimately, the Ivy League style—especially in its historical form—is indeed part of the American stylistic heritage. Though it may be less prominently featured than cowboy or military styles within the Western Americana trend, it remains a key hue in the overall palette, adding smarter touches (like a varsity jacket, crest-emblazoned cardigan, or vintage tie) to the ensemble.

After this historical overview, one practical question arises: how can you adopt the Americana style today without slipping into costume territory? Good news: Americana style is more relevant than ever and easily integrates into a modern wardrobe. The Americana outfits trend frequently returns in magazines and on runways—as seen in the recent 2024 enthusiasm for the cowboycore look or in major designers’ collections inspired by the West. Beyoncé, for instance, paid tribute to Levi’s blue jeans in one of her stage outfits, while designer Pharrell Williams presented a highly Western-inspired collection at Louis Vuitton (cowboy hats, fringe jackets). Proof that the yee-haw style has indeed swaggered onto the streets in recent years.

To master this style effortlessly, aim for a subtle balance between standout pieces and restraint. The idea isn’t to turn yourself into a Western movie character, but rather to elegantly weave a few key items into your everyday looks. A double-breasted blazer worn over a jacquard denim western shirt, paired with fine-striped trousers and classic loafers, is a perfect contemporary reinterpretation of Americana tailoring. You could also take a more sportswear approach by pairing a Filson flannel shirt with retro sweatpants and a modern western jacket by Needles.

If you’re inspired by the motorsport universe, try a vintage racing jacket with authentic Levi’s jeans and embroidered suede western boots. For a feminine touch in this realm, combine a Fox Racing motocross jersey with high-waisted vintage 501 jeans and Ralph Lauren leather cowboy boots for a bold, up-to-date contrast.

"Dress carefully: a few wrong moves and your closet will buck you like a wild horse," GQ humorously warns. Nowhere more than in Americana does it all come down to nuance and restraint. Opt for subtlety: replace a heavily patterned western shirt with a plain off-white or cream T-shirt to balance the outfit.

Authenticity and the patina of time are at the heart of the Americana aesthetic. As one trusted style guide advises: “Whenever you can go vintage, do it. Retro is a big part of Americana style.” Whenever possible, favor vintage or heritage pieces like worn-in selvedge Levi’s 501s, a second-hand military jacket, or a vintage bandana. These add instant credibility and the character that only real wear can offer.

Finally, don’t be afraid to mix influences: integrate a utilitarian piece into a traditional preppy outfit (like a Carhartt jacket over an Ivy League sweater), or elevate a simple streetwear look with a vintage Perfecto jacket or an authentic trucker cap. A navy blazer combined with raw jeans and a chambray shirt, for example, effortlessly leans into a refined, timeless Americana register.

In short, adopting the Americana style today is about embracing strong values: authenticity, freedom, durability. In an age of throwaway fashion and fleeting trends, Western Americana offers a return to essentials—with solid pieces, rich in history and meaning. This style allows for true personal reinterpretation: everyone can create a look that honors the past while staying firmly modern.

To build out your wardrobe further, check out our complete guide in the dedicated article on Americana clothing brands—a full panorama of historical brands and contemporary labels reinventing this stylistic heritage with care… a mission we proudly share. Don’t hesitate to explore our product collection as well: Western Americana Apparel. We offer a curated selection of trucker and 5-panel caps, leather key clips and belts, as well as thoughtfully designed T-shirts and hoodies that embody the spirit of modern Americana.

In conclusion, Western Americana is a movement rich with layered narratives—the cowboy, the laborer, the soldier, the rocker, the student—all woven into a stylistic mythology unique to the United States. From its utilitarian roots to its rise as an international fashion phenomenon, it has endured through the decades while retaining its appeal. Dressing in Western Americana today is, in a way, reliving the legend of the West and the American Dream—while asserting your individuality. Whether through subtle touches (a belt, a vintage jacket) or a carefully orchestrated full look, anyone can make this style their own and write their own chapter in the great Americana story.

Follow us on Instagram

FAQ