American motorsports — whether car or motorcycle racing — hold a unique place in the collective imagination of the United States. For over a century, the culture of motorsports has developed at the crossroads of industry, the American dream, and an unshakable spirit of freedom. From the first dirt track races in the early 20th century to today’s modern supercross shows, this culture has generated its own myths, visual symbols, and dress codes. In this article, we trace chronologically how American motorsport culture was built, how it evolved, and how it now inspires the contemporary Americana aesthetic.

.jpg)

The roots of American motorsports go back to the industrial boom of the early 20th century. While the automobile was still in its infancy, a few pioneers pushed their machines to the limit in wild dirt track races. Even before World War I, dirt track racing thrilled the American public and became widespread by the 1920s.

These races took place on simple dirt ovals — often repurposed horse racing tracks — where cars and motorcycles slid side by side in clouds of dust. These local competitions, inexpensive and spectacular, laid the foundations of a popular motorsport embedded in county fairs and agricultural festivals.

At the same time, the automobile industry was taking off. Henry Ford, determined to build an affordable car for everyone, perfectly illustrated the link between industry and competition: in 1901, unable to convince investors, he decided to prove himself on the track. Against all odds, Ford won a race in Detroit on October 10, 1901, beating the famous driver Alexander Winton — a victory that earned him the fame and capital needed to found the Ford Motor Company.

As he would later say, “The public refused to see the automobile as anything but a toy for speed… so we had to race.” This anecdote shows how, from the very beginning, automobile racing served as a technological showcase and a driver of innovation in industrial America.

In 1909, Indiana became home to a visionary project: the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, a massive brick circuit built on former cornfields. It was there that the first Indy 500 took place on May 30, 1911 — a 500-mile (800 km) race that would become a national tradition. The winner of this inaugural edition, Ray Harroun in his Marmon “Wasp,” recorded an average speed of about 120 km/h — far from today’s performances, but extraordinary for the time. The Indy 500 quickly established itself as “the greatest race in the world,” embodying America’s enthusiasm for speed and large-scale popular events.

On the two-wheeled side, the first American motorcycle competitions also emerged early. Brands like Indian and Harley-Davidson, founded around 1901–1903, were already entering their bikes into races. The spectacular board track races (held on steeply banked wooden velodromes) attracted massive crowds in the 1910s, despite their extreme danger. In 1924, the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) was founded — a sign that motorcycle racing was also finding its organization. Traveling “motordromes” and hill climb events helped forge the early foundations of a U.S. motorcycle sport culture, although it remained on the fringes compared to car racing.

Finally, even in these early days, one idea began to take root: the car and the motorcycle as symbols of freedom. While in 1900 the automobile was still a toy for the wealthy, Henry Ford and others dreamed of making it an accessible means of emancipation. Their success in mass industrialization would gradually make that dream a reality.

America discovered in the automobile a new frontier: the ability to go anywhere, independently. Very quickly, “the open road” became a symbol of freedom, adventure, and the American Dream. This association between motor vehicles and individual freedom, initially limited to a few pioneers, would only grow stronger in the decades to come.

.jpg)

In the 1930s and ’40s, American motorsports gained deeper popular roots, driven by the blue-collar culture of small towns and rural communities. During Prohibition (1920–1933), an unexpected phenomenon even contributed to the rise of auto racing: the underground drivers of bootleggers (alcohol smugglers) modified their cars to outrun the police. These supercharged vehicles and their fearless drivers gave rise, after Prohibition ended, to informal “stock car” races in the American South.

On rudimentary oval tracks, lightweight Ford coupes and makeshift Chevrolet sedans raced against one another. The public success was so great that Bill France Sr. brought together the key players of these races and founded NASCAR (National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing) in February 1948. Stock car racing thus became a structured sport, with its first stars (Herb Thomas, Lee Petty, etc.) being former weekend drivers elevated to local hero status. The expression “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday” emerged during this time: manufacturers realized that race victories directly boosted showroom sales.

Meanwhile, the Indianapolis 500 continued to build its legend. After a hiatus during World War II, the race resumed in 1946 with undiminished fervor. Tens of thousands of spectators poured into the Speedway each year, solidifying Indy’s status as the “Mecca” of American auto racing.

Starting in 1950, the race was even briefly included in the Formula 1 World Championship (though European drivers rarely participated), giving it international prestige. The 1950s saw the triumph of the legendary front-engine roadsters, driven by aces like Bill Vukovich and a young A.J. Foyt at the beginning of his career.

On the motorcycle side, the postwar era saw the rise of a dynamic biker culture. Many World War II veterans, familiar with Harley or Indian military bikes from the front lines, returned home seeking camaraderie and adrenaline. They formed motorcycle clubs (MCs) to ride together and extend their brotherhood beyond the battlefield. In July 1947, a biker gathering in Hollister, California, descended into disorder — an incident amplified by the press and dubbed the “Hollister Riot.”

Though the story was exaggerated, it crystallized the image of the outlaw biker in the public imagination. Hollywood seized on the narrative: the film The Wild One (1953) featured Marlon Brando as the leader of a rebellious motorcycle gang.

Brando — wearing a black Schott leather Perfecto jacket, blue jeans, and engineer boots — embodied the 1950s biker look: a style of romantic outlaw that would inspire generations of young rebels and rockers. Ironically, few Americans at the time had ever seen a real biker gang, but Brando cemented the archetype: from then on, the “black leather jacket” became synonymous with the biker.

Beyond the aesthetic, motorcycle racing was also becoming more organized: in 1954, the AMA launched the Grand National Championship, combining flat track races (oval dirt tracks) and road races. Flat track motorcycle racing, in particular, became immensely popular in the 1950s and ’60s — sometimes even more so than pure speed racing on circuits. This championship saw Harley-Davidson and Indian face off in a fierce rivalry dating back to the prewar era — until Indian disappeared in 1953, leaving Harley with uncontested dominance.

Riders like Joe Leonard (three-time AMA champion in the ’50s) thrilled crowds on the dirt tracks of state fairs. Flat track racing established itself as the quintessential American motorcycle sport of the time, held on half-mile or mile-long ovals where bikes slid through corners with handlebars turned sideways. These images of riders drifting through the turns, wearing boots and open-face helmets, became part of the sport’s visual mythology.

At the same time, the automobile entered 1950s popular culture like never before. The postwar era was marked by economic boom and the rise of suburban housing. The car, symbol of comfort and mobility, became a central element of the American dream. Owning a car, driving on the newly built Interstate Highway System, going on a road trip along Route 66 — all became new rites of freedom. For young people especially, the car was a means of emancipation — they cruised through town, drove to the drive-in movies in convertible Chevrolets. The automobile had become “a powerful symbol of personal freedom and social success” in the prosperous America of the postwar years.

Hollywood captured the mood: in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), James Dean challenges his peers in a tragic car race (the infamous “chicken run” toward the cliff), a cult scene linking cars, youth, and rebellion. Music followed suit: rock’n’roll songs celebrated flashy cars and speed — think “Maybellene” by Chuck Berry (1955), or the wave of early ’60s “hot rod” songs by the Beach Boys like “Little Deuce Coupe.” A whole American “Car Culture” was taking shape, where the automobile was not just a vehicle but a way of life — and motorsport was its extreme showcase, the place where limits were tested.

.jpg)

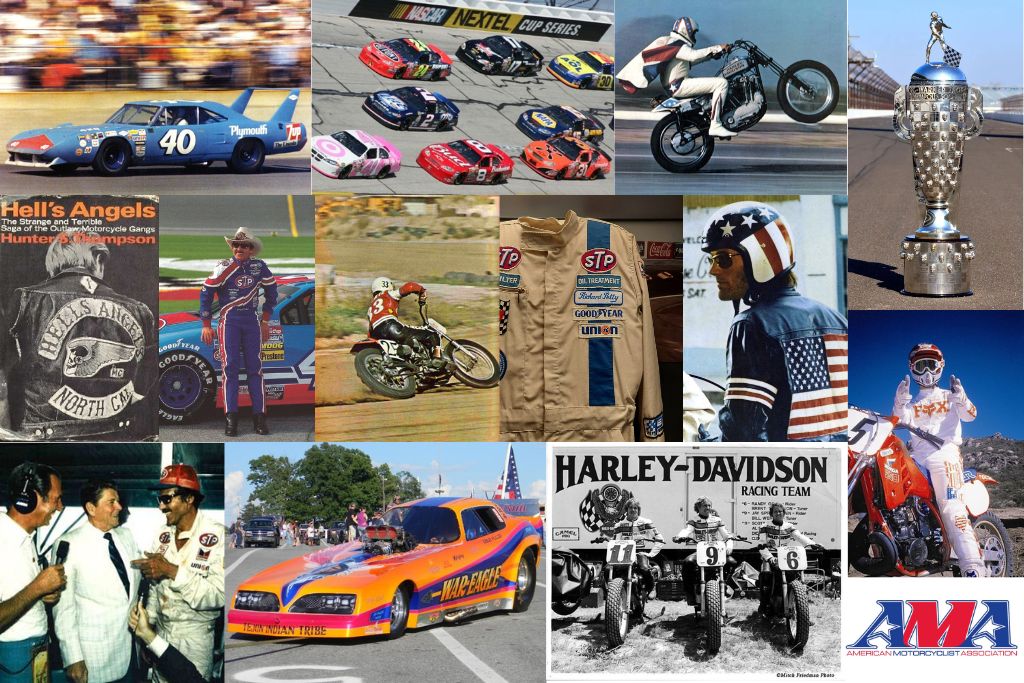

The 1960s–70s represent an eclectic golden age for American motorsports, blending technical innovation, popular fervor, and countercultural appropriation. On four wheels, two major disciplines gained momentum: stock car NASCAR racing grew to national scale, while the monstrous Can-Am (Canadian-American Challenge Cup, 1966–1974) pushed engineering to its limits.

The Can-Am series, held in the U.S. and Canada, allowed for virtually every technical excess: massive unrestricted engines, turbochargers, movable wings, aerospace materials — “the only rule in Can-Am is that there are no rules,” as the saying goes. Crowds flocked to witness these roaring, futuristic prototypes. Eyewitnesses described the cars as “powerful, loud, and spectacular,” thrilling the baby-boomer generation with their sheer noise and fury.

Star drivers — Bruce McLaren, Denny Hulme, Mark Donohue, Jim Hall, and others — became legends, and some machines (like the McLaren M8B or the 1,100-horsepower Porsche 917/30 turbo) left lasting impressions with their jaw-dropping performances. Though short-lived, the Can-Am’s aura helped make the 1960s–70s a “glorious and limitless” era in the collective memory of American auto racing.

In NASCAR, the sixties marked the entry of Detroit’s major manufacturers into the fray. Ford, GM, and Chrysler seized upon the growing televised popularity of races to promote their muscle cars. This was the era of the speed-shaped Plymouth Superbird and Ford Torino “Talladega,” and of legendary duels on the Daytona superspeedway.

Iconic figures rose to the top: Richard Petty, nicknamed “The King,” racked up victories (he would win 7 championships between 1964 and 1979), instantly recognizable in his sky-blue #43 Plymouth adorned with the STP logo. With his cowboy hat and sunglasses, Petty embodied the approachable NASCAR hero beloved by the Southern working class. Another ace of the era, Mario Andretti, achieved the rare feat of winning the Indy 500 in 1969 and the Formula 1 World Championship in 1978 — a symbol of Italian-American success and all-around racing talent.

America also saw the emergence of its first heroines: in 1967, Janet Guthrie became the first woman to race in NASCAR, cautiously opening the door to minorities in a male-dominated world. In 1963, Wendell Scott became the first African-American driver to win a NASCAR Grand National race (the predecessor of the Cup Series) — a victory achieved in the midst of the civil rights struggle, ignored at the time and only officially recognized much later. These breakthroughs remained rare, but they showed that motorsports were (very slowly) beginning to reflect the diversity of American society.

On two wheels, the late ’60s were marked by the rise of a new discipline imported from Europe: motocross. In 1966–67, promoters organized the first U.S. tours of European champions (the Inter-Am Series), sparking enthusiasm for this spectacular sport of jumps and ruts. On July 8, 1972, one event would change everything: at the legendary Los Angeles Coliseum, the first stadium motocross race was held, dubbed the “Superbowl of Motocross.”

In front of over 29,000 spectators, a 16-year-old teenager, Marty Tripes, won the inaugural event — the birth of what would become Supercross. This concept of urban stadium motocross saw immediate success: just two years later, the AMA launched the official Supercross Championship (1974). In only a few years, Supercross became one of the most popular forms of motorcycle racing in America, drawing young crowds into football and baseball stadiums each winter.

The event combined sport and American-style showmanship — stadium lighting, hyped-up announcers, rock music — to the point where Supercross appealed well beyond just motorcyclists. This triumph of off-road adrenaline fit perfectly into the American tradition of motorsport as spectacle.

As motocross spread, the “outlaw” biker culture reached its media peak. In the mid-’60s, Hunter S. Thompson’s gonzo novel Hell’s Angels (1966) and various scandalous news stories fueled the dark legend of clubs like the Hells Angels. Easy Rider (1969), Dennis Hopper’s cult film, offered a more idealized vision: two long-haired bikers ride across the country on Harley-Davidson choppers, searching for spiritual freedom to a backdrop of psychedelic rock.

The film — with a soundtrack that introduced the classic Born to be Wild by Steppenwolf — turned the motorcycle into a symbol of hippie rebellion and anti-establishment spirit. This romantic vision deeply influenced the youth of the era: riding across the American landscape by motorcycle became an act of defiance against conformity.

Ironically, reality soon caught up with fiction: in 1969, at the Altamont concert, Hells Angels hired as security killed a spectator, marking the symbolic end of the peace-and-love utopia. But in the collective imagination, the association “motorcycle = defiance of authority” was now firmly sealed.

The ’70s also saw the rise of a larger-than-life pop icon: Evel Knievel, motorcycle stuntman. Clad in glittery jumpsuits patterned with the U.S. flag, Knievel performed insane jumps — over buses, the Caesars Palace fountains, even the Snake River Canyon in a rocket-bike — in front of millions of television viewers.

He embodied American daring and the cult of risk, while his star-spangled suit and tricolored helmet became instantly recognizable. Toys in his likeness, comic books, and a kitschy patriotic fashion style extended his cultural impact. Though operating outside of “official” motorsport, Evel Knievel helped glamorize motorcycles and firmly root them in mainstream pop culture.

On four wheels, pop culture was just as involved: Hollywood produced numerous films glorifying speed or staging legendary car chases (Bullitt in 1968 with Steve McQueen and his roaring Ford Mustang in the streets of San Francisco, Vanishing Point in 1971, Smokey and the Bandit in 1977 celebrating the art of outrunning the law in a Pontiac Trans Am).

Television joined in by the late ’70s with The Dukes of Hazzard (1979), a series where two daredevils in an orange Dodge Charger (the “General Lee”) performed stunts and wild chases through the Deep South. The figure of the “road rebel” — whether a fearless NASCAR driver, philosophical biker, or vigilante behind the wheel — became a lasting fixture in the American imagination.

Aesthetically, the ’60s–’70s left a strong mark. It was the era of brightly colored machines covered in logos: race cars now proudly displayed sponsor stickers (oil companies, cigarette brands, equipment manufacturers). In NASCAR, for example, iconic liveries emerged — Richard Petty’s red and blue STP Plymouth, Bobby Isaac’s black “Good Ol’ Boys” Dodge Charger.

Black-and-white checkered flag patterns, stylized racing numbers, and motorsport-inspired typefaces became common in the graphic design of the time. Among drivers and teams, Nomex racing suits adorned with advertising patches became standard, as did full-face helmets personalized with color stripes — like Knievel’s star-spangled helmet or A.J. Foyt’s red helmet with a star motif.

A distinctly American “motorsport” visual language was taking shape — a blend of patriotism (U.S. flags painted on car bodies or helmets), visual excess, and blue-collar pride. The paddocks of the era exuded a unique charm: chrome-plated trucks, pit boxes with retro signage, western-style lettering on team panels — a whole visual folklore now viewed with nostalgia, inspiring museums, exhibitions, and designers alike.

Want to get the full picture of Americana? Check out our article: What is Western Americana?

.jpg)

At the turn of the 1980s, American motorsport underwent a dual transformation: on one hand, it became firmly rooted in mass culture through television and corporate sponsorship; on the other, new car subcultures began to emerge outside official circuits. NASCAR, in particular, entered its media boom.

In 1984, President Ronald Reagan attended a Cup Series race in person — a first for a sitting president. Stock car legends like Dale “The Intimidator” Earnhardt (seven-time champion between 1980 and 1994) became working-class heroes, soon joined by a new generation led by Jeff “Wonder Boy” Gordon, a young prodigy in the rainbow-colored DuPont car who claimed three titles in the ’90s.

Broadcast weekly on television, NASCAR races entered households across the Southern and Midwestern United States — historical strongholds of the discipline. The fan base exploded, and NASCAR expanded far beyond its Southeastern roots, building new ovals as far as Chicago and Kansas City. Cars, now true “rolling billboards,” were covered in vivid sponsor logos — from cigarettes and motor oils to sodas.

By the 1990s, the phenomenon reached its peak: every team flaunted billion-dollar sponsors, drivers became brand ambassadors, and merchandising reigned supreme — team-branded caps, jackets, and die-cast cars sold by the millions. Dale Earnhardt’s black No. 3 Goodwrench Chevrolet and Jeff Gordon’s multicolored DuPont Chevrolet became visual icons, printed on thousands of T-shirts and collectibles. NASCAR had stepped out of its niche and joined the ranks of America’s top-tier sports business.

At the same time, off-road motorsports experienced their golden age in the 1980s–90s. The AMA Supercross Championship filled baseball and football stadiums during winter, while outdoor motocross events brought excitement to the summer months. Charismatic champions like Jeff Ward and Rick Johnson dominated the ’80s, paving the way for the era of off-road superstars. In the 1990s, Jeremy McGrath embodied this energy: the Californian racked up no fewer than seven AMA Supercross titles between 1993 and 2000, earning the nickname “King of Supercross.”

His spectacular style (he popularized the nac-nac jump) and flair for showmanship drew massive crowds and boosted Supercross’s TV ratings. McGrath became a media phenomenon, transcending the motorcycle world — appearing in films, on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, and even having a video game named after him — proof that Supercross had entered American pop culture. In his wake emerged a young prodigy, Ricky Carmichael, who began to shine in motocross (AMA champion as early as 1997) and in 250cc Supercross by the end of the decade. Later nicknamed “The GOAT” (Greatest of All Time) for his total dominance of the sport around the turn of the 2000s, Carmichael represented the new generation that would eventually dethrone McGrath.

On the business side, a full-blown motocross gear economy developed: brands like Fox Racing and Thor became iconic with their brightly colored outfits. Motocross kits of the ’90s featured aggressive graphic patterns, oversized logos, and neon colorways — all signature traits of the decade’s aesthetic. These flashy designs quickly spread beyond the track: motocross apparel began influencing streetwear fashion, with people proudly wearing neon Fox jerseys or Thor caps even if they’d never touched a dirt bike.

On asphalt, another extreme discipline continued its rise: drag racing. In the 1980s–90s, NHRA (National Hot Rod Association) drag racing events — straight-line acceleration races — continued to attract a dedicated, insider audience. The premier categories, Top Fuel dragsters (long, streamlined missiles) and Funny Cars (aerodynamic cars with “phantom” bodies), kept pushing the boundaries of physics.

On March 20, 1992, driver Kenny Bernstein broke the mythical 300 mph barrier (~482 km/h) in just 4.82 seconds over a quarter mile — a historic first that made national headlines. These machines burn nitromethane and devour 400 meters in a deafening roar, cheered on by fans captivated by their sheer excess. Visually, drag racing left a lasting impact, influencing graphic design far beyond the track.

Since the 1970s, Funny Car bodies had become true works of rolling art, painted by brush masters like Kenny Youngblood or Don Kirby. In the 1980s, despite the arrival of major corporate sponsors, these designers managed to combine corporate logos with bold color schemes while preserving the flamboyant hot rod spirit.

Bodies adorned with stylized flames, aggressive typography, goofy mascots — the over-the-top dragster aesthetic spread throughout American visual culture. Flame motifs, popularized in the ’50s–’60s by artists like Von Dutch, made a roaring comeback on custom cars in the ’80s–’90s — so much so that Pontiac even released a stock Firebird with a gigantic firebird decal on the hood. This fiery, speed-obsessed imagery became a universal graphic language, reproduced on T-shirts, tattoos, concert posters, and even rock album covers.

Drag racing itself remained somewhat niche, overshadowed by NASCAR in terms of mainstream visibility during the ’90s. But its subculture stayed vibrant — populated by legendary figures like John Force (multiple Funny Car champion) — and continued to embody a certain idea of blue-collar, nitro-fueled rebel America.

By the mid-1990s, a car revolution was brewing far from the official circuits: the rise of “tuning” culture and street racing. Taking advantage of the massive influx of affordable Japanese coupes into the U.S. market (Honda Civic, Toyota Supra, Acura Integra, Nissan 240SX, etc.), thousands of young people began transforming these lightweight machines into turbocharged beasts. This movement, known as the import scene or tuner culture, was born on the streets of Southern California before spreading eastward (New Jersey, Florida…) and into the Midwest.

As early as the late ’80s, Los Angeles saw the rise of wild night runs where old Datsun 510 coupes raced against heavily modified Mazda RX-7s. In 1990, organizer Frank Choi launched the very first official event dedicated to “imports” — Battle of the Imports — at Los Angeles County Raceway, drawing around sixty tuned Asian cars and a crowd of 500 spectators.

The following year, attendance doubled, prompting Choi to quit his job and devote himself entirely to these semi-legal races. Soon, tuners and clubs began organizing across the country. On the East Coast, abandoned dragstrips in New Jersey or Pennsylvania were reclaimed on weekends for import drag racing events, where drivers — often from Puerto Rican, Dominican, or other Latino communities — took center stage.

At the heart of this scene, people exchanged mechanic tips and rare imported parts — often through Japanese magazines like Option or Best Motoring. Tuning became a lifestyle: Civics were lowered, turbocharged, fitted with chrome rims and booming subwoofers, their windshields proudly displaying NOS (nitrous oxide system) stickers. The culture was especially embraced by young Asian-American and Hispanic communities, who saw it as a space for expression and community pride.

By the late ’90s, spontaneous parking lot gatherings (car meets) drew hundreds of personalized cars, while California-based workshops like Greddy or HKS USA made a fortune selling turbo kits and sports suspensions. The hype caught Hollywood’s attention: in 1998, a Vibe Magazine article about New York street racers inspired a film project. A few years later came Fast and Furious (2001), a mainstream adaptation of this nocturnal L.A. subculture, where modded Civics and Supras clashed in illegal street races.

Fiction met reality: the film immortalized the visual codes of ’90s tuning — underglow neon lights, flashy vinyl wraps, roaring engines — and cemented street racing as a fully-fledged part of American automotive mythology.

By the end of the 20th century, American motorsport had infiltrated every corner of pop culture. Hollywood multiplied its tributes to racing: Days of Thunder (1990) featured Tom Cruise as a flamboyant NASCAR driver, exposing the world to the paddock folklore of Daytona. A few years later, Supercross: The Movie (2001) and Driven (2001) tried to capitalize on the trend, respectively diving into the worlds of motocross and IndyCar.

Action cinema also revived the art of wild car chases: Gone in 60 Seconds (2000), a remake of the 1974 original, spotlighted “Eleanor,” a souped-up 1967 Ford Mustang GT500, in a high-octane pursuit straight out of every street racer’s fantasy.

In music, automotive references roared just as loud. Mötley Crüe’s hard rock anthem Kickstart My Heart (1989) opens with the sound of an engine and explicit lyrics — “Top fuel funny cars, a drug for me,” screams frontman Vince Neil — symbolizing the adrenaline rush that drag racing represents in the rock imagination.

In 1990s hip-hop, racing aesthetics also burst onto the scene, both in lyrics and visuals: rappers compared their flow to high-performance engines, flaunted their rides in music videos, and adopted racing attire. A striking example is Ghostface Killah’s (Wu-Tang Clan) 1999 video Mighty Healthy: the New York MC appears wearing a NASCAR jacket plastered with logos (notably DuPont, Jeff Gordon’s sponsor) — a piece designed by streetwear label FUBU — paired with motocross-inspired caps and jackets.

This convergence between rap and motorsports extended to the stage as well: nu-metal singer Kid Rock would perform wearing a full NASCAR pit crew uniform, while the crowd headbanged to music sampled with the roar of race cars.

Finally, urban fashion in the late 1990s and early 2000s embraced the imagery of American motorsport. NASCAR driver jackets, once sold only at racetracks to die-hard fans, became trendy pieces in the streets. Hip-hop brands like FUBU and Sean John launched collections directly inspired by racing codes: bomber-style jackets embroidered with sponsor patches, reimagined mechanic suits, and caps featuring checkered flags and iconic race numbers.

Wearing an official M&M’s, DuPont, or Goodwrench jacket became hype — even if you couldn’t tell an oval track from a road course. The trend was less about motorsport knowledge and more about style, as shown by the popularity of vintage Dale Earnhardt T-shirts in the ’90s. This fashion wave was first sparked by the African-American community — Tupac famously wore NASCAR Starter jackets, and Missy Elliott blended motocross gear with streetwear — before spreading to the broader public.

By the early 2000s, countless young people proudly wore rainbow-colored Jeff Gordon jackets or Honda Racing caps. Even high-end designers eventually adopted these codes: in the 2010s, labels like RHUDE and Kith paid tribute to the ’90s by reissuing garments featuring NASCAR iconography — T-shirts printed with race cars, retro-style racing jackets, and more.

New York designer Teddy Santis, through his brand Aimé Leon Dore, collaborated with Porsche to infuse rally aesthetics from the ’70s–’90s into his collections — proof of motorsport’s lasting influence.

Thus, by the dawn of the 2000s, the circle had closed: born in underground scenes or regional fervor, the various American motorsport cultures — from Southern stock car to Californian tuning, from freestyle supercross to vintage drag racing — had all, in one way or another, conquered the national and international stage, leaving a lasting imprint on fashion, music, and collective imagination.

The United States was experiencing a true golden age of auto-moto sports, where the popular fervor of the racetrack coexisted with the street-level cool of those behind the wheel or handlebars — foreshadowing the modern era, where the engine reigns supreme both on the track and in the streets.

American motorsport culture didn’t just produce champions and events — it gave rise to an entire aesthetic and a series of iconic objects whose influence extends far beyond the sporting world, touching fashion and lifestyle alike.

First, there are the machines themselves. Some race cars and motorcycles have become true design icons. Take the 1965 Ford Mustang — popularized through the Trans-Am series and Hollywood films — it remains a symbol of American individualism and raw energy. The muscle cars of the ’60s–’70s (Chevrolet Camaro, Dodge Charger, Pontiac GTO…) embody a style that enthusiasts still try to emulate or restore today.

On the motorcycle side, the Harley-Davidson XR750 flat track bike (introduced in 1970) is a rolling myth, considered “the most successful racing motorcycle in AMA history.” Its stripped-down lines, peanut tank, oval number plates, and rigid frame represent the archetype of American-made dirt bikes. Custom choppers inspired by Easy Rider (extended forks, high handlebars, flamboyant paint jobs) influenced both production motorcycles and an entire segment of motorcycle fashion (fringed jackets, “Captain America” helmets, etc.). As for the Indy and Can-Am cars of the ’60s, many ended up in museums — their aerodynamic shapes and vintage colors inspiring posters, collectible die-casts, and even designer furniture.

Then there’s the clothing and accessories directly drawn from the paddocks. Motorsport popularized garments that crossed the gates of the circuit to enter the streets. The leather Perfecto jacket, originally created in 1928 for motorcyclists, owes much of its global fame to American bikers and Marlon Brando — it has since become a staple of rebellious fashion.

The raw denim Levi’s 501, sturdy and utilitarian, was an essential part of the 1950s biker uniform and has become a universal symbol of American cool alongside the Perfecto. Black engineer boots — tall work boots adopted by bikers as early as the 1940s — remain closely tied to the retro biker aesthetic.

In the world of auto racing, the canvas mechanic’s jumpsuit, complete with embroidered name and team patches, inspired the workwear style. Today, wearing a mechanic-style jumpsuit or a vintage garage shirt nods to that heroic era when people wrenched on engines in parking lots before a race.

Mesh trucker caps and plaid flannel shirts, worn by pit crews and off-track drivers in the ’60s, have become streetwear staples. Even perforated leather driving gloves and aviator sunglasses have left the driver’s seat to become iconic pieces of vintage-inspired fashion.

Another cult object of American motorsport: the race jacket embroidered with logos. In the 1980s–90s, many brands released jackets inspired by NASCAR or drag racing, featuring multicolored leather sleeves and sponsor patches (Goodyear, STP, Valvoline…).

These flashy jackets were a massive hit in American urban fashion, particularly embraced by the hip-hop community during the 1990s. Artists like Tupac and Mobb Deep were seen wearing NASCAR jackets emblazoned with M&M’s or racing team logos, transforming a sportswear item into a bold fashion statement. Thus, the “racewear” trend was born.

This phenomenon accelerated in the 21st century with the growing enthusiasm for vintage Americana. Numerous fashion brands began tapping into the motorsport heritage to create collections with a modern edge. For example, the New York streetwear label Supreme collaborated directly with Fox Racing, the iconic motocross gear brand, releasing in 2018 a full line of MX gear (jerseys, pants, helmets, chest protectors) worn in the streets.

The collection faithfully reproduced the motocross uniform aesthetic — so much so that off-road gear became a full-fledged runway trend, picked up even by luxury houses like Dior and Saint Laurent. Fox Racing, founded in California in 1974, is a perfect example: once a maker of parts and apparel for dirt bike riders, it is now a global style reference. Its “fox head” logo is worn in cities by youth who’ve never set foot on a motocross track.

Traditional American brands also rode this wave. Tommy Hilfiger, the champion of U.S. preppy style, has repeatedly integrated racing-inspired elements into his collections: he has sponsored racing teams (notably in Formula 1) and more recently, in 2023, announced a partnership as official outfitter of a future American F1 team (Cadillac/Andretti), with an entire lifestyle collection centered on racing. Hilfiger sees this as an extension of his “Modern Americana” concept applied to motorsports.

In this same spirit, emerging labels are reinterpreting the essence of American motorsport through fresh lenses. Drover Club, for instance, offers a contemporary take on Western Americana by blending two foundational American universes: vintage motorsport and cowboy/rodeo culture. Bold colors, innovative materials, and daring design come together in their Western Americana apparel collection.

Guess Jeans, already in the ’90s, used vintage Americana settings in its photo campaigns, including motorcycles and muscle cars — famously, a black-and-white ad featuring Claudia Schiffer posing pin-up-style on a Harley. More recently, L.A. streetwear designers like RHUDE made motorsport references central to their identity: RHUDE released luxury racing jackets echoing team apparel and even collaborated with automotive giants like Lamborghini and Pirelli.

New York–based Aimé Leon Dore stood out by restoring vintage Porsche cars and designing a full wardrobe inspired by the ’60s–’70s (quilted driver jackets, racing sunglasses, leather gloves) to complement the project. Brands like Off-White and Gucci have also, at times, incorporated checkered flags, sponsor patches, or racing suit cuts into their collections — proof that the theme holds widespread fascination.

Beyond clothing, motorsport culture permeates the lifestyle world: retro garage-themed interior decor, cafés styled after Route 66 diners, tattoos of pistons and biker eagles — and of course, a booming merchandising market. Vintage caps, T-shirts from legendary races, reissued race posters, die-cast Harley and hot rod models for home decoration…

Specialized magazines and media — from Hot Rod Magazine, founded in 1948, to Easy Riders in the ’70s — have carried this imagery and helped spread it beyond the enthusiast circle.

Why, in 2025, does this thread of American heritage still captivate so deeply? More than just a sport, “Made in USA” motorsport embodies timeless values. First, there’s the appeal of the vintage and the authentic: in an increasingly digital world, returning to loud, smelly, mechanical machines brings a tangible sense of nostalgia.

Restoring a 1955 Chevy or riding a classic Indian Chief means reliving a piece of American history and rediscovering the essence of old-school engineering. That explains the growing popularity of retro gatherings like the Goodguys Hot Rod Show, the Race of Gentlemen (period vehicle races on the beach), or the many Cars & Coffee events where muscle cars and vintage bikes share the spotlight.

Then there’s the adrenaline — the thrill. Motorsport remains one of the few realms where danger is brushed up against. Whether it’s on a dirt oval, a quarter-mile dragstrip, or a Supercross stadium, the risk and speed deliver a raw excitement that continues to fascinate. Even non-participants are drawn to that vicarious thrill — as evidenced by the massive success of more recent film franchises like Fast and Furious (since 2001, which popularized the street racing scene) or racing video games.

This rebellious, defiant spirit tied to cars and bikes remains a romantic ideal, especially in a heavily regulated society. Wearing a biker jacket or a vintage drag racing tee is a way to declare a bit of that rebellion.

Finally, the cultural and aesthetic dimension of American motorsport continues to inspire contemporary creators because it is rich in strong symbols: the notion of freedom (the open road, the ride), camaraderie and community (biker clubs, NASCAR fans as “family”), patriotic folklore (the American flag waved at start ceremonies, the national anthem, etc.), and even the meritocratic dream (any small-town kid could become a dirt track hero if he was handy enough).

These themes still resonate — and their imagery is abundantly reused in social media, photography, and music. Think of the countless music videos showing muscle cars doing burnouts, or models posing in minishorts on retro bikes in front of vintage diners: it’s an entire visual language of Americana that speaks instantly to a global audience.

Today, American motorsport culture is far from frozen — it is constantly being reimagined. Museums like the Harley-Davidson Museum or the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum keep the historical flame alive by exhibiting vintage machines and memorabilia.

Online archives (old Daytona 500 videos, documentaries on early pioneers) allow new generations to discover this rich legacy. In graphic design, old-school elements are making a comeback: race number–inspired fonts, retro patch motifs, racing colors (royal blue, fire red, checkered flag patterns) reappear on sneakers and streetwear logos.

Even modern motorsports in the U.S. pay tribute to their roots. When MotoGP returned to the Indy circuit in 2008, the posters featured a 1950s pin-up style. NASCAR organizes Throwback Weekends, during which cars wear vintage liveries from past legends. Events like Flat Out Friday in Milwaukee revive old-school indoor flat track racing, with vintage motorcycles and a full rockabilly vibe.

In this way, the Americana Motorsport spirit lives on — not only on the track but as a fully-fledged lifestyle, where nostalgia, culture, and speed meet in a timeless visual and emotional experience.

Sources:

This article draws on a wide range of historical, cultural, and specialist sources surrounding American motorsports and its aesthetic and social influence. The origins of NASCAR, its popular roots, and the figure of Bill France Sr. are based on official archives available via the NASCAR website and the ISC Archives & Research Center. The history of motorcycle flat track racing, the Harley-Davidson vs. Indian rivalry, and the AMA Grand National Championship is documented through institutions such as the Harley-Davidson Museum, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, Corporate Ford and specialist media including Cycle World.

The aesthetics associated with the culture — XR750 motorcycles, choppers, 1960s–70s muscle cars — were contextualized through archival material from magazines like Hot Rod Magazine and Road & Track. The influence of motorsport on contemporary fashion — particularly through brands like Supreme, RHUDE, Aimé Leon Dore, Guess, Fox Racing, and Tommy Hilfiger — was analyzed using articles and critiques published in Highsnobiety, GQ, Motortrend, NHRA, Britanica, Smithsonian magazine, Townfairtire,

Major cinematic and documentary references such as The Wild One (1953), Rebel Without a Cause (1955), On Any Sunday (1971), and Fast & Furious (2001) were also included to illustrate the impact of motorsports on the American imagination. Finally, current events like the Race of Gentlemen, NASCAR's Throwback Weekends, and Flat Out Friday helped root this culture in a living continuity — one that blends nostalgia with contemporary reinvention.

Follow us on Instagram

FAQ