The history of the cowboy doesn’t begin in Hollywood. Long before becoming an emblematic figure of the American imagination, he was a horseback cattle herder, heir to the Hispanic-Mexican vaqueros, living to the harsh rhythm of the West. While cinema and popular culture have largely shaped his image, the cowboy’s historical reality is far more complex—marked by diversity, labor, migration, and social tensions. By retracing his origins, his role in the conquest of the West, his living conditions, and the many representations he has inspired, this article offers a more complete reading of a figure that has become central to Americana culture.

The image of the lone cowboy roaming the prairie is inseparable from American culture, but his roots go much deeper than the Far West. Long before the cowboy emerged in the 19th century, there was the vaquero—a term derived from vaca, “cow” in Spanish—who appeared as early as the 16th century with the Spanish colonization of the continent.

Starting in 1519, the Spanish introduced the first cattle herds and horses to the Americas, training expert riders to herd them. These vaqueros were often Mesoamerican natives taught by Spanish missionaries and settlers in the arts of horseback riding and lassoing, adapting the long Iberian equestrian tradition to the vast stretches of the New World.

Over the centuries, a true vaquero culture flourished. Spanish ranches expanded from Mexico into Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and California, where by the late 18th century, missions relied on the labor of vaqueros to control thousands of wild cattle. Their expertise was essential in these pioneering societies: they could tame the wildest horses, braid their own rawhide lassos (lazo in Spanish), and master the art of catching stray cattle on the fly.

Many terms now inseparable from cowboy vocabulary in fact come from Spanish, bearing witness to this Hispanic heritage: rodeo (originally meaning “to gather cattle”), lasso, lariat, sombrero (ancestor of the Stetson), chaparreras (which became “chaps”), and rancho, among others.

It was in the mid-19th century, following the Mexican-American War (1846–1848) and the annexation of Texas by the United States, that the figure of the American cowboy began to emerge by incorporating this vaquero heritage. English-speaking settlers then poured into the prairies of Texas and the Southwest. Often, they took over former Mexican ranches and employed the vaqueros already in place, while learning from them the techniques of cattle herding and lasso work.

This blending of cultures—Hispanic, Indigenous, and Anglo-American—gave birth to the cowboy as he would soon enter American history. Around 1865, after the Civil War, millions of Texas longhorns (long-horned cattle descended from the herds introduced by the Spanish) roamed semi-wild across the lands of Texas. These countless herds and the growing demand for beef in the East would offer the young nation the opportunity to develop an unprecedented cattle industry—and propel cowboys to the forefront of the conquest of the West.

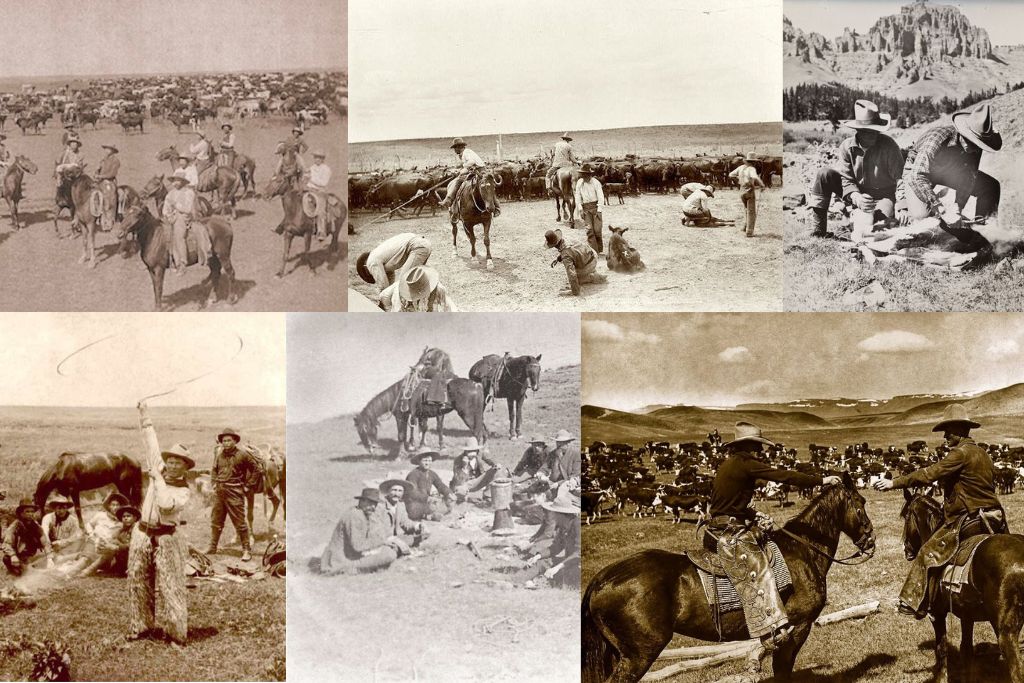

Unlike the gunslinging cowboy of the movies, quick to draw his revolver at the slightest provocation, the daily reality of a 19th-century cowboy was far less glamorous and far more grueling. Most were simply ranch laborers paid by the job: a ranch cowboy earned, on average, one dollar a day, with basic food and shelter provided. Days began before dawn and stretched late into the night, spent almost entirely in the saddle.

During long cattle drives, a herd of 2,000 heads could be entrusted to just a dozen cowboys, who had to watch the animals constantly. The work was exhausting—15 hours a day under sun or storm—and monotonous, punctuated by repetitive tasks like gathering scattered cattle, monitoring water holes, or repairing fences and pens.

The environment and the climate were among the cowboy’s main adversaries. On the trail, the dust stirred up by thousands of hooves coated them in a thick layer “like fur,” despite the bandana tied around their face. After weeks of inhaling dust from the herds, many coughed up blackened sputum for days once they reached rest.

In contrast, torrential rains turned the earth into a sticky mire through which men and animals trudged with difficulty. By day, the blazing heat of the plains could create mirages and dehydrate horses; by night, the cold pierced through exhausted cowboys sleeping on the ground, wrapped only in a thin blanket. The saddle wore the body down: after hours of riding, men suffered from blisters, aching backs, and the constant presence of insects.

Though danger was ever-present, it wasn’t what you might expect. “Death was never far from the cowboy,” historian Patrick Dearen would later write, but it came far more often from the frenzied horns of a stampeding steer than from an Indian arrow or an outlaw’s bullet. A badly timed horse kick, a rattlesnake underfoot, or a foot caught in the stirrup during a fall—these were frequent causes of serious injury.

Indian attacks or gun duels were, in reality, more the exception than the rule. Most cattle drives crossed Indigenous lands without incident, sometimes in exchange for a toll of a few cents per head paid to local tribes for the right of passage.As for cowboy towns, far from the constant chaos depicted by Hollywood, they often enforced strict regulations: many banned carrying firearms within city limits, requiring visitors to hand over their revolvers at the entrance. Likewise, ranch owners would not tolerate brawling, drunkenness, or dueling—though these are shown as commonplace in Westerns. A cowboy who broke the rules risked being fired on the spot.

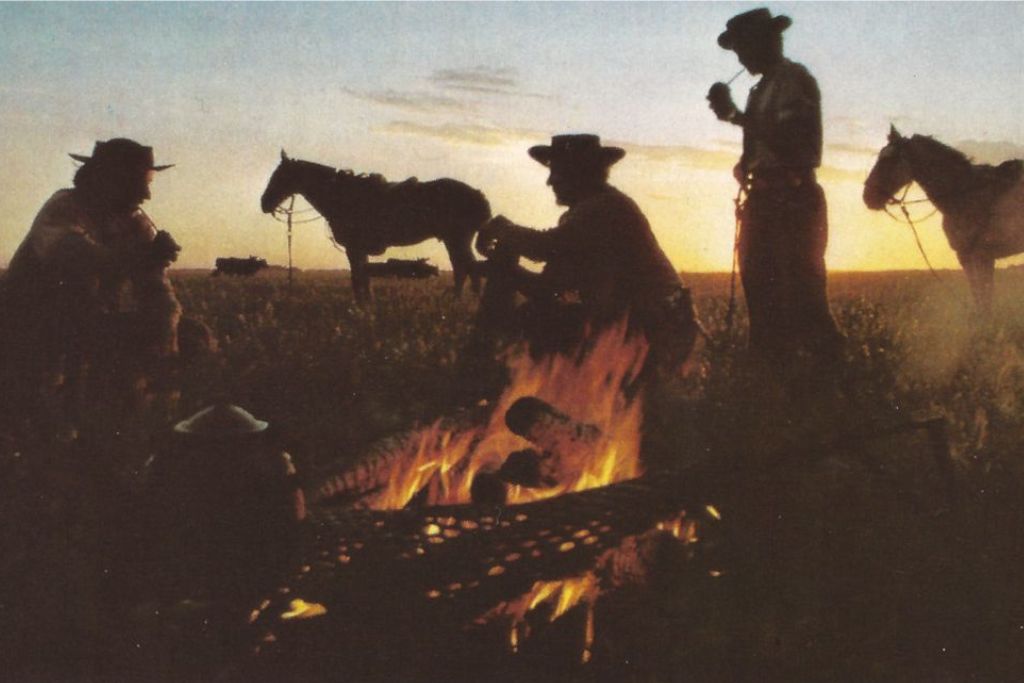

In the evening, around the campfire near the chuckwagon (the convoy’s kitchen cart), the cowboy’s fare consisted of black coffee and a meager ration of beans, hard biscuits, salted pork, or aged cheese. To fight the boredom of the nightly watch, they sang melancholic ballads about “the hardships of life on the trail,” played the harmonica, told often bawdy stories, and sometimes even organized “stag dances”—makeshift dances between men in the absence of female partners.

Because the cowboy world was almost exclusively male—women were exceedingly rare on cattle drives—it fostered both strong camaraderie and a harsh environment where sensitivity had little room. In this masculine world of solitude and risk, cowboys prized resourcefulness and endurance above all.

The cowboy’s fierce individualism is no myth: isolated for weeks on end, he had to rely on himself and the mutual aid of his companions to survive nature’s whims. This was the real life of cowboys—a humble, exhausting, and dangerous job, far removed from the glamorous epic so often portrayed on screen.

Want to get the full picture of Americana? Check out our article: What is Western Americana?

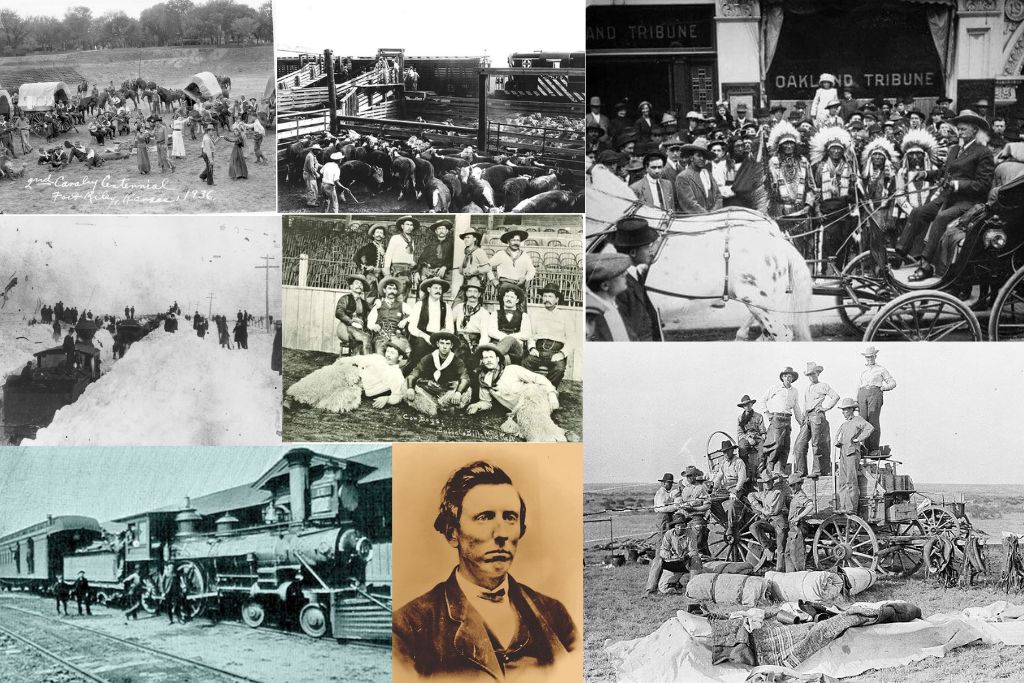

From the mid-19th century to the late 1880s, cowboys played a central role in the westward expansion and economic development of the young United States. After the Civil War (1861–1865), the country found itself with millions of cattle scattered across the Texas plains and a booming meat market in the rapidly growing industrial cities of the East. Thus began the legendary era of the great cattle drives across the plains.

In 1866, for example, Texan ranchers organized the first major northbound drive, herding their cattle over hundreds of kilometers to Kansas, where the nearest railway line could transport the animals to Chicago. Railroad towns like Abilene, Wichita, and Dodge City quickly became thriving “cattle towns”: Abilene shipped over 35,000 head of cattle in its very first year of operation in 1867, after businessman Joseph McCoy built a livestock loading dock there.

Famous trails were etched across the map of the West: the Chisholm Trail to Kansas, the Western Trail to Dodge City, and the Goodnight-Loving Trail that reached as far as Wyoming. For roughly three decades, tens of millions of animals were thus driven from Texas ranches to northern pastures or rail depots, in what became one of the largest animal migrations ever orchestrated by humans.

The work of cowboys directly accompanied—and in part made possible—the American “Frontier,” that is, the colonization of the continent’s interior lands. They opened routes across largely uncharted territories, helped feed the growing populations of new states, and supplied meat to rapidly expanding metropolises.

Socially, the cowboy was both a modest laborer and a key player in the transformation of the West: managing vast herds on unfenced lands required a near-military organization of ranches and cattle convoys. Each major drive demanded a division of tasks (scouts at the front, flank riders to contain the herd, drag riders to push the stragglers, cook and wrangler), thus foreshadowing modern logistics and transportation systems.

Cowboys also contributed to the rise of Western towns: when herds arrived, saloons, hotels, and shops in the cattle towns flourished by welcoming exhausted cowboys armed with three months’ pay—ready to spend it on whiskey and various “entertainments.” Dodge City, Abilene, and Tombstone became famous as much for the cattle that passed through as for the sometimes volatile atmosphere that reigned during those stopovers (from which much of the Wild West mythology would later emerge).

It’s important to note, however, that the cowboy’s golden age was relatively brief. Historians estimate that the classic period of the open range and major cattle drives lasted only about two decades—from 1866 to the late 1880s. Several developments brought it to an end. First, the arrival of barbed wire in the 1870s revolutionized the West: ranchers could now enclose vast areas at low cost, depriving roaming herds of the open spaces they once enjoyed and ending the era of free-range routes.

At the same time, railroads continued expanding across the continent: by the 1890s, nearly every ranching region was close to a railway line, rendering the long drives to distant stations obsolete. Finally, devastating winters discouraged any remaining attempts to keep cattle in the open: the winter of 1886–1887—remembered as the Big Die-Up—saw hundreds of thousands of cattle freeze to death, trapped by snowstorms and penned in by newly built fences. This cocktail of overgrazing, enclosure, and extreme weather marked the end of the “Cattle Kingdom.”

Starting in the 1890s, extensive ranching gave way to a more sedentary form: herds were kept in fenced pastures, ranches became smaller but better managed, and the cowboy’s job evolved into year-round ranch work rather than a nomadic, long-haul life. Many cowboys settled down; some founded small farms of their own.

Others continued the adventure by heading farther west (to Montana or Wyoming) or by participating in the first organized rodeos to keep the tradition alive (as early as 1882, Buffalo Bill Cody staged a show of roping and bronc riding in North Platte, often considered the first rodeo). In a sense, the cowboy figure had fulfilled its historical mission: in the span of a single generation, he helped shape the American West, paving the way for the era of settled ranchers, barbed wire, and railroads. But this was only the beginning of his life as a national myth.

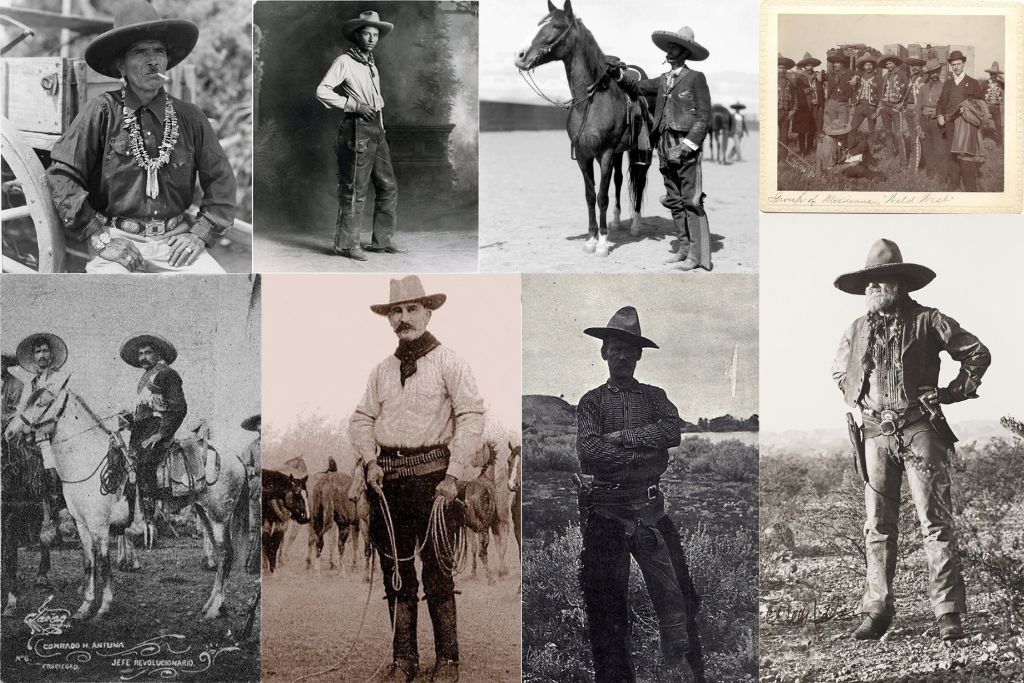

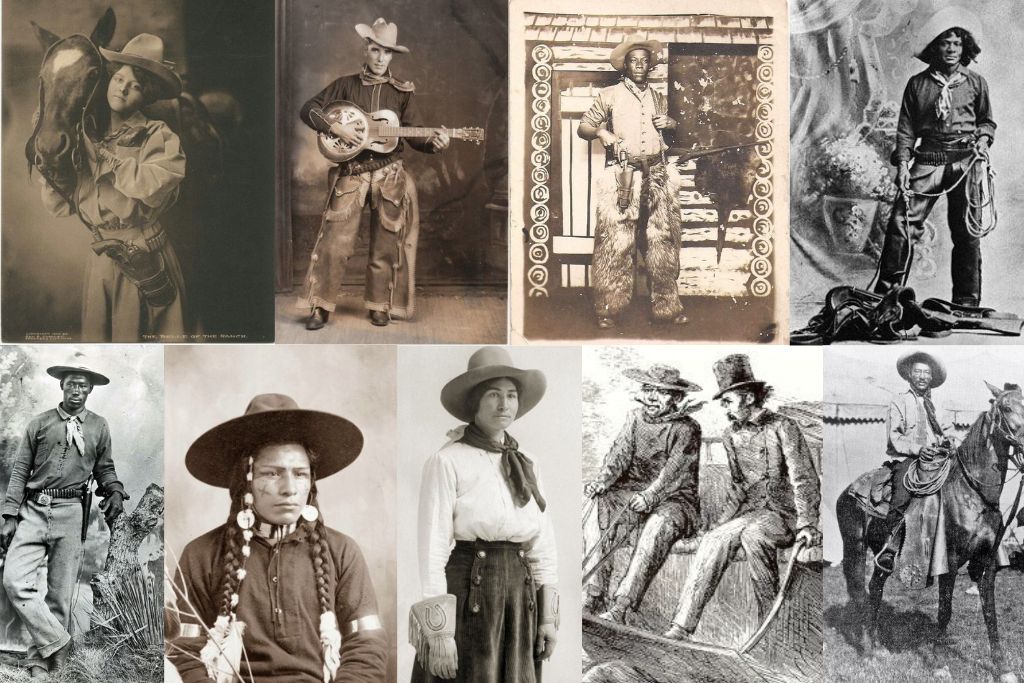

While Hollywood long gave us a standard image of the cowboy—a white man, solitary and righteous—the historical reality was far more diverse. Among the tens of thousands of cowboys who roamed the West in the 19th century, all ethnic and social backgrounds of America at the time were represented. It’s estimated that roughly one in four cowboys was African American, and a similar number were Hispanic (mainly Mexicans or Tejanos, Texans of Mexican descent).

After the Civil War, many newly freed former slaves headed West in search of a better life and a measure of freedom. Rapidly expanding ranches lacked manpower and readily hired Black or Mexican cowboys—often for lower wages than their white counterparts, but offering them a rare chance at autonomy for the time.

The Black cowboy was one of the largely unrecognized driving forces of the Westward expansion. Figures like Nat Love, born a slave in Tennessee and later a lasso expert who published an autobiography in 1907, illustrate these remarkable trajectories. Nat Love, who adopted the nickname “Deadwood Dick,” claimed to have learned Spanish, won rodeo contests, and survived numerous adventures—though his account likely embellishes his already colorful life.

Others, like Bose Ikard (a Black cowboy who inspired a character in the novel Lonesome Dove) or the famous Bill Pickett (inventor of the “bulldogging” steer wrestling technique in rodeo), highlight the significant role African Americans played in Western culture. For many former slaves, becoming a cowboy offered an escape from the violent segregation of the post–Civil War South: on the trails of Texas or Kansas, a Black man on horseback could earn a degree of respect—if not full equality.

Of course, racism was not absent in the West—the very term cowboy is believed to have originally been used pejoratively to refer to Black men (white ranchers preferred terms like cowhand or cowpuncher at the time). Nevertheless, on the ground, the grueling nature of the work often fostered interracial camaraderie: “Every cowboy depended on his partners to survive,” noted historian Roger Hardaway, referring to how men of different backgrounds had to work closely together in hostile environments.

Alongside Black and Anglo-Saxon cowboys were, naturally, Hispanic cowboys—Mexicans or Californios—often direct heirs of the original vaqueros. Mexican expertise in horse training and lasso work was highly respected: it was not uncommon for a Texan ranch to employ a vaquero foreman to supervise newly hired Anglo-American recruits, so deeply rooted were Mexican techniques in the trade.

In some parts of the Southwest, Hispanic cowboys even made up the majority of the workforce until the late 19th century. They too, however, faced discrimination and rarely attained the role of ranch foreman, despite their skills.

Other, more unexpected groups also took part in the cowboy epic. Native Americans, for example, sometimes joined cattle drives as trackers or stable hands. After the Indian Wars of the 1870s, some young men from Plains nations—Cheyenne, Comanche, Pawnee—chose to become cowboys rather than endure the poverty of the agricultural reservations imposed on them.

One rancher even praised his Pawnee cowboys as “the best in the world” at leading cattle through Indian Territory (Oklahoma). There were also women cowboys, though they were a clear minority: most were daughters or wives of ranchers who took part in farm work (riding to round up cattle, especially when the men were away on drives), or in rare cases, adventurers who disguised themselves as men to get hired on cowboy crews.

These female figures, like Charley Parkhurst (a celebrated stagecoach driver) or later Lucille Mulhall (one of the first rodeo cowgirls in the early 20th century), remained on the fringes of mainstream history but prove that the West was not exclusively male.

Thus, the cowboy workforce was a patchwork—reflecting America’s mosaic. However, this diversity was long overlooked in popular narratives. Neither the dime novels of the 19th century nor the films of the 20th gave due credit to the thousands of Black, Mexican, or Native cowboys who helped build the West.

Only recently has their contribution begun to be properly recognized, through the work of historians, museums (such as the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, or the National Cowgirl Museum in Texas, which also honors the women of the West), and even recent works of fiction that revalue cowboys of color (such as the 2021 film The Harder They Fall, with a majority African-American cast inspired by real-life figures).

The truth is that the history of the cowboy belongs to all Americans—no matter their origin—even if the legend hasn’t always told it that way.

How did the modest, dust-covered cattleman become the legendary hero we know today? The cowboy myth began to take shape at the end of the 19th century, just as the era of the great cattle drives was fading. The main architect of this myth was the entertainment and popular publishing industry. As early as the 1870s, the Eastern public became fascinated with romanticized tales of the West. “Dime novels” flooded the market with stories of cowboys and outlaws. One of the star figures was Buffalo Bill Cody, a former army scout and buffalo hunter, whose life was heavily fictionalized by writer Ned Buntline.

In 1869, Buntline published Buffalo Bill, King of the Border Men, the first in a long series of heroic tales about Cody, which would turn him into a true national celebrity. Over the next two decades, more than 1,700 stories featuring Buffalo Bill were published—along with countless booklets about Billy the Kid, Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, and other Western figures. These tales, often far removed from reality, portrayed an idealized cowboy: brave, gallant, quick to defend the widow and the orphan, a master marksman, and a man of irreproachable morality—in short, a modern-day knight roaming the prairie.

Buffalo Bill Cody didn’t stop at being a character in a novel. In 1872, he was convinced by Ned Buntline to take the stage and play himself in a theater production, Scouts of the Plains. The success was immediate. Cody, alongside other living legends like “Wild Bill” Hickok and Texas Jack, toured Eastern theaters dressed in fringe-lined costumes, recounting his exploits (liberally embellished). Building on this experience, Buffalo Bill had a brilliant idea: to create a traveling mega-show recreating the atmosphere of the frontier.

In 1883, he launched Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, which would tour for thirty years across the United States and then Europe. The show was a blend of circus, historical reenactment, and rodeo: real cowboys demonstrated lasso tricks and mustang taming; real Native Americans (including the famous Sitting Bull at one point) played their own roles by attacking fake stagecoaches; and sharpshooters like the legendary Annie Oakley dazzled crowds with their feats. Buffalo Bill himself, triumphant on a white horse, opened each show galloping to greet the crowd, Stetson hat in hand—an iconic silhouette that would imprint itself on the collective imagination.

These Wild West Shows toured the world, presenting millions of spectators with a romanticized version of the West: everything was larger-than-life, from six-shooter duels to stagecoach attacks, even including scenes like the reenactment of the Battle of Little Big Horn (!). Admittedly, historical accuracy suffered, but the legend of the righteous cowboy was elevated on a global scale.

At the same time, another phenomenon helped cement the myth: the rise of the rodeo as a sport. Originally informal contests among cowboys to see who was best at lassoing or staying atop a wild horse, rodeos became full-fledged spectacles by the late 19th century.

Buffalo Bill himself had organized a Western festival in North Platte, Nebraska, in 1882—considered the first official rodeo. Soon after, annual events were established (Cheyenne’s rodeo in 1897, Prescott’s in Arizona), where former trail cowboys would compete in front of spectators.

Rodeos thus kept cowboy traditions alive in the industrial era, while feeding the mythology: they enshrined the image of a man capable of taming nature (breaking a mustang, controlling a wild bull) and displaying physical bravery without fail. The rodeo became, in a way, the athletic counterpart of the legend—crystallizing the heroic cowboy figure in the modern arena.

In the 20th century, Hollywood took over, firmly embedding the cowboy as a cultural icon. From the silent era on, and especially with the rise of talkies, the Western became a dominant genre. Hundreds of films featured sheriffs and outlaws, high-noon duels, and horseback rides across Monument Valley. Hollywood softened and standardized the cowboy image: through actors like John Wayne or Gary Cooper, he became manly but principled, faster than his shadow, and a defender of justice against villains (often caricatured Native Americans or lawless bandits).

These films also popularized an entire visual language—boots, Stetson, holstered Colt—that made the cowboy an instantly recognizable symbol worldwide. But in glorifying the myth, Hollywood also perpetuated simplistic clichés. Early Westerns depicted nearly all cowboys as white men, erasing the real diversity of the frontier.

They also exaggerated the violence: shootouts and saloon brawls became obligatory scenes, whereas in reality, such incidents were rare and even discouraged, as we've seen. The distortion was so obvious that, by 1962, filmmaker John Ford could criticize it in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, with the famous line: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Nevertheless, the fictional cowboy would remain firmly imprinted in the public’s mind. Beyond cinema, radio and later television extended the fascination (popular Western series in the 1950s–60s, children’s heroes like the Lone Ranger). The cowboy became the archetype of the American hero, bearer of positive values (courage, sense of justice, fierce independence), but also a vehicle for stereotypes (the white cowboy versus the “redskin” Indian—a tired trope of countless Westerns).

Along the way, some female figures like Calamity Jane or Annie Oakley also gained legendary status through literature and entertainment, proving that the myth could accommodate a few heroines in this male-dominated universe.

Thus, by the early 1960s, the entire world had a very specific—albeit largely fantasized—image of the cowboy. He had become a pop culture icon: sung in country ballads, drawn in comic strips and posters, turned into a marketing symbol (the famous Marlboro Man, introduced in 1954, was a striking example of the lone, rugged cowboy figure used to sell cigarettes).

In the span of a few generations, the anonymous cattleman of the West had transformed into a universal myth—a process in which fiction largely overtook reality, to the point that the two are sometimes indistinguishable in the public imagination.

It’s impossible to talk about the cowboy without picturing his distinctive silhouette: wide-brimmed hat, leather boots, sturdy pants, neckerchief... This iconic outfit was not originally a costume, but the result of an evolution dictated by the demands of life on the range—long before it was adopted by fashion and American pop culture.

In the mid-19th century, cowboys mostly wore functional clothing inherited from Mexican vaqueros or frontier laborers. The hat, for instance, varied by region: in the arid South, broad-brimmed sombrero-style hats offered protection from the sun, while in the windy plains of Wyoming, cowboys preferred shorter brims to prevent them from blowing away.

But in all cases, it was a deep-crowned felt hat that served many purposes—scooping water, watering a horse, fanning a campfire, or signaling from afar. In 1865, a hatter named John B. Stetson designed a model specifically adapted to the West: the Boss of the Plains, which would become the legendary Stetson.

By the 1890s, the high-crown, wide-brimmed Stetson was worn by the majority of cowboys in the United States. (Fun fact: despite its popularity, the most common hat in the West around 1880 wasn’t the Stetson but... the bowler hat! Indeed, many cowboys also lived in town or frequented saloons and adopted the bowler, which was more fashionable among the general population. Only those “in the field,” spending their lives on horseback, wore the practical Stetson daily.)

Another essential element: cowboy boots. Initially, herders wore heavy work boots similar to those of lumberjacks or miners. It wasn’t until the mid-1870s that a boot specifically designed for intense riding appeared. Its tall shaft (up to mid-calf) protected the leg from brush, snake bites, or rubbing against the horse’s flank.

Thick leather and decorative stitching weren’t just for looks: the embroidery helped stiffen the shaft to keep it from collapsing, providing better support. The toe was narrow and pointed—not out of vanity, but to easily slip in and out of the stirrup. As for the boot’s angled heel, slanted forward, it served a vital function: preventing the foot from sliding too far into the stirrup and allowing for a quick release in case of a fall, reducing the risk of being dragged by a panicked horse.

Conversely, that high, curved heel made long walks quite uncomfortable—further proof that these boots were made for riding, not pounding pavement!

The cowboy’s pants also evolved. Until the 1880s, many wore California-style trousers inherited from vaqueros: woolen, snug at the waist and thighs but flared at the bottom, held up without a belt (sometimes with suspenders). Durable cotton fabrics came later.

In the 1870s, Levi Strauss, a merchant in San Francisco, began selling denim trousers reinforced with metal rivets at stress points (pockets, fly)—an innovation by his partner Jacob Davis to prevent tears during hard labor. When they patented these riveted pants in 1873, the ancestor of the blue jean was born—unknowingly reshaping both cowboy identity and American fashion forever.

Initially favored by miners, these tough denim pants reached ranches, where cowboys appreciated their durability and flexibility. Other brands would follow (Wrangler, Lee), and by the early 20th century, jeans had replaced the old wool trousers on ranches.

To fit this new cut, belt loops were added to jeans in the 1920s (as cowboys had previously preferred suspenders over belts). The cowboy blue jean was born—and would soon transcend the West to become a universal garment in the 20th century.

Up top, cowboys wore long-sleeved shirts made of cotton, flannel, or wool—often checkered or solid-colored. These thick shirts offered protection from the burning sun by day and the cold by night. Blue was especially common in the 1860s–70s, thanks to surplus army fabric left after the Civil War.

Over their shirts, they often wore sleeveless vests, ideal for adding warmth without hindering movement, and especially useful for their accessible pockets while riding (hard to reach pant pockets on horseback). Jackets or coats were rare while riding, as they were cumbersome—except in freezing weather, when cowboys wore thick sheepskin coats.

Finally, a few iconic accessories completed the look. The bandana—a bright cotton neckerchief—was endlessly versatile: filtering dust, shielding the neck from the sun, wiping sweat, dressing wounds, even doubling as a makeshift halter or potholder for a hot pan. Chaps—short for chaparreras—were thick leather leg coverings strapped over trousers to guard against scratches (thorns, bushes, barbed wire) and cold.

Imported once again from vaquero tradition, chaps could be made of cowhide, goatskin, or even hairy leather (the spectacular wooly chaps of angora used in Nevada). They gave cowboys their instantly recognizable silhouette and became a powerful visual symbol of the Western. Other essentials included leather gloves (crucial for roping or handling barbed wire without injuring the hands) and, of course, spurs—fastened to the heels of boots, used to communicate with the horse.

It’s worth noting that although these garments were primarily utilitarian, they soon carried a sense of personal style unique to cowboys. Even in the wild West, cowboys liked to stand out with touches of flair: decorative stitching on boots, a brightly colored bandana, an embroidered shirt for Sundays...

With the arrival of film and country singers yodeling in glittering outfits, the cowboy look was further embellished—think of Roy Rogers’ fringe shirts or the rhinestone suits of the “singing cowboys” of the 1940s–50s. But such extravagance was mostly reserved for the stage. The average working cowboy remained understated: keeping worn clothes for labor and only pulling out a nice shirt for a town dance or family portrait.

Whatever the case, the cowboy’s wardrobe outgrew its original context. In the 20th century, Western wear infiltrated American fashion—and then global style. The blue jean, first adopted by workers, became the go-to pants for youth and eventually every social class.

Pointed cowboy boots were reinterpreted by designers and remain associated with a rebellious, adventurous spirit. The Stetson hat, still worn on ranches, has also been adopted by American presidents, rock stars, and even haute couture designers. Periodically, fashion revives Western elements: fringe jackets, embroidered shirts, oversized belt buckles return to the runway.

There’s a symbolic charge in the cowboy’s attire that continues to fascinate: slipping on jeans and a Stetson is like putting on a piece of the West’s soul—wrapping oneself in a symbol of rugged freedom. The cowboy outfit, born from practical needs, has become a mythical uniform of America—constantly reinvented between rustic authenticity and fashion-forward interpretation.

Many brands today offer modern takes on the Americana aesthetic. One such brand is Drover Club, which brings a contemporary reading of Western Americana by blending two foundational universes of the American imagination: vintage motorsport and the world of cowboys and rodeos. Bold colors, innovative materials, and daring design converge in its Western Americana apparel collection.

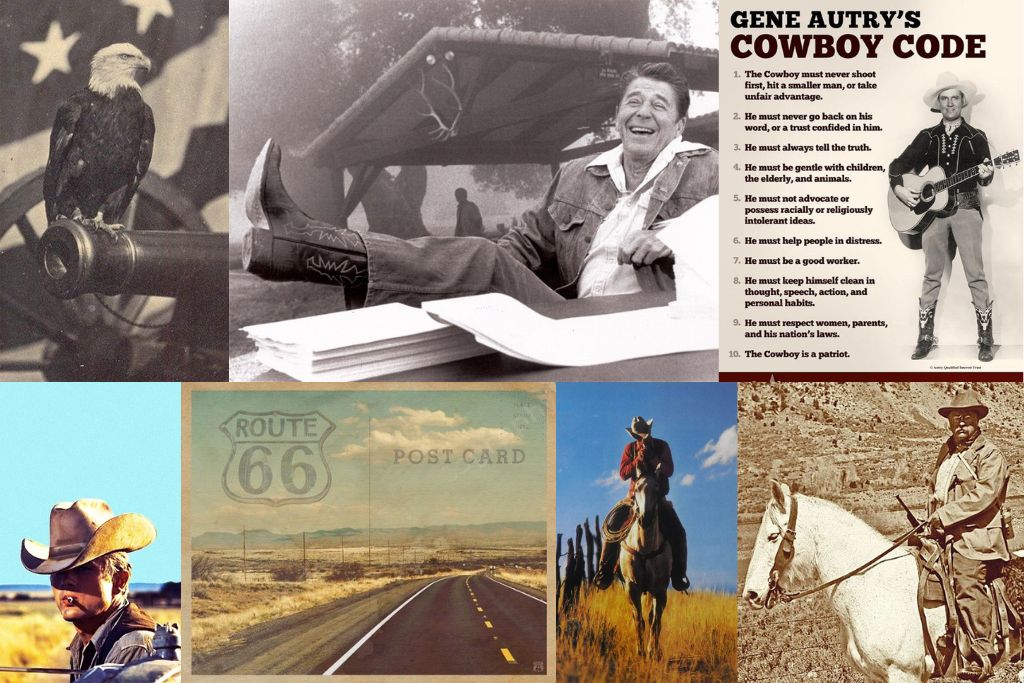

The cowboy holds a special place in the American imagination because he has become a true national myth, embodying values that the United States readily claims as its own. Among America’s pantheon of symbols—alongside Uncle Sam and the bald eagle—the cowboy stands out as the incarnation of fierce individualism, conquering freedom, a spirit of adventure, and the self-reliance so dear to American culture.

The silhouette of a lone man on horseback, framed by the vastness of the prairie, evokes the possibility of forging one’s own path, far from authority and the constraints of civilized society. This image directly echoes the Frontier and Manifest Destiny: the idea that the nation was forged by constantly pushing the frontier, thanks to courageous, enterprising, and independent individuals.

As early as the late 19th century, thinkers like historian Frederick Jackson Turner theorized the importance of the Frontier in shaping the American character—and the cowboy naturally emerged as its popular hero. In the early 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt, fascinated by the West (where he had once owned a ranch), promoted the cowboy image as an antidote to urban decadence: in his view, the modern man needed to toughen up in the open air, and the cowboy embodied the ideal of virile manhood, forged by untamed nature.

In his writings, Roosevelt extolled the courage, honor, and resilience of cowboys, contrasting them with what he saw as the softness of East Coast city-dwellers. Thus, the cowboy was elevated to the status of founding myth, embodying a masculine ideal and moral uprightness. Traits like straightforward honesty, loyalty, and the belief in “playing fair” even in a lawless world—all of this formed part of the cowboy ethic, popularized for instance through the “Cowboy Code of Honor” promoted by singer-actor Gene Autry (never lie, help the weak, respect your country, etc.).

Politically and culturally, the cowboy gradually became an idealized symbol of the American everyman. In the years following the Civil War, some Southern editorialists portrayed the Western cowboy as the antithesis of the bureaucratic Easterner or the dependent freedman—elevating the cowboy as the ultimate defender of individual liberty against government interference.

In the 20th century, it’s no coincidence that presidents identified with this figure: Ronald Reagan, a former Western film actor, often posed as a cowboy on his California ranch to associate himself with the values of toughness and pioneer simplicity. Likewise, John Wayne—Western film icon and influential conservative voice—was often seen as the onscreen embodiment of the “American Way.”

Internationally, the cowboy has come to symbolize the American—sometimes in a caricatured way (we still label reckless or undisciplined behavior as “cowboy”). But for many Americans themselves, he represents a legacy to be proud of: that of a nation born from the conquest of vast territory by men and women whose only weapons were courage and determination.

The cowboy also carries a certain nostalgia. In an increasingly urban and high-tech world, he embodies a connection to nature and the simple life of the land. The image of the lone cowboy at sunset is a kind of memory of a pastoral, free America—untamed by modern constraints. This is why it remains so present in culture, especially in country music—where the cowboy figure and prairie longing are recurring themes—and in events like Western festivals, historical reenactments, and of course, the rodeos that still thrive today.

The cowboy lies at the heart of Americana—the term for the aesthetic and cultural references that are quintessentially American (from Route 66 to baseball to Delta blues). We collect his artifacts (ornate saddles, antique spurs, Wild West Show posters), and wear his symbols in fashion and decor because they tell a founding story.

Beyond the U.S., the cowboy has projected an image of America that is both fascinating and complex. Fascinating for its romanticism of freedom and wide-open spaces—but complex, because it was built on harsher realities (territorial conflicts, bison extermination, the subjugation of Indigenous peoples—all aspects often omitted from the myth).

In this sense, the cowboy is an ambivalent hero: at times celebrated as a crusader for civilization against savagery, at others criticized as the armed hand of ruthless conquest. This duality keeps him at the center of study and debate—and reinforces his presence in the national consciousness.

Ultimately, the cowboy still defines Americana because he symbolizes an essential part of the American identity—the independent, brave, and resourceful pioneer. In a country of immigrants with diverse roots, the cowboy offers a shared narrative, a common mythology centered on freedom and challenge.

He is to America what the samurai is to Japan, or the knight to medieval Europe: a figure both real and legendary, crystallizing collective ideals.

Is the cowboy merely a relic of the past? Certainly not. Even today, real cowboys still ride across American ranches. While techniques have evolved—ATVs and pickups have partly replaced horses for herding, and pastures are now fenced—thousands of ranchers and agricultural workers in rural parts of the West continue to carry on the cowboy trade. They take part in local rodeos, uphold the practices of extensive ranching, and pass down skills like roping, breaking horses, and horseshoeing from one generation to the next.

Some ranches even offer tourists the chance to experience a real “drive” during immersive stays—a sign that the legend still attracts those in search of authenticity. The modern cowboy does exist, even if he’s swapped his Colt for a smartphone and might head home in a pickup instead of on horseback after a long day’s work.

Even more surprising is the way the cowboy figure is undergoing a true cultural and stylistic revival in the 21st century—sometimes in unexpected places. A movement often referred to as the “Yeehaw Agenda” in the U.S. is reviving the Western aesthetic in pop culture, especially among Black American artists. In 2019, young rapper Lil Nas X made headlines with his viral hit Old Town Road, a mix of trap and country, whose music video shows him dressed in all-black leather cowboy gear, riding a horse through a hybrid urban-Western setting. The song’s global success reignited interest in the overlooked history of Black cowboys and showed that Western imagery still resonates with a new generation. That same year, Beyoncé released a country track (Daddy Lessons) and in 2021, she launched a fashion collection—Ivy Park x Adidas—themed around rodeo, blending streetwear with Western references.

More recently, Pharrell Williams—artist and designer—has also made his love for the cowboy universe explicit. In 2024, as the new Men’s Creative Director for Louis Vuitton, Pharrell unveiled a collection in Paris inspired by the Wild West, complete with a faux Western town set and real Black cowboys walking the runway in luxury attire. Fringe jackets, cactus motifs, bolo ties, and turquoise belt buckles made their way onto haute couture runways, testifying to the cowboy style’s enduring influence.

That same year, the clothing brand Gap collaborated with legendary tailor Dapper Dan—a key figure in hip-hop fashion—to create a line combining streetwear with Western elements, such as denim shirts embroidered with miniature cowboy hats. Dapper Dan, himself a Black Harlem native, emphasized the importance of this gesture by stating: “We were among the original cowboys, and we’re also the faces of the future—we are the urban cowboys.” A way of reclaiming the cowboy legacy for Black urban culture and reintegrating the descendants of those long excluded from the myth.

This current enthusiasm for Black cowboys and Western fashion is more than just a surface trend: it reflects a deeper process of cultural and identity reclamation. By restoring visibility to the African American cowboys long erased from history—by transforming them into fashion muses and film characters—modern America is revisiting a neglected chapter of its past and weaving it into its present.

Events like the Compton Cowboys (a group of Black riders in California working with youth from underserved neighborhoods) or the numerous Black rodeos across the country show that tradition is still alive—active across time, generations, and colors. Likewise, Latino communities in the Southwest continue to preserve the culture of the charro (the Mexican version of the cowboy, with its own equestrian tournaments and ornate attire)—further proof that the cowboy legend is enriched by many lineages.

The cowboy has also found new ground in modern media: reimagined in contemporary cinema (Brokeback Mountain reinterpreted the myth through a queer lens; No Country for Old Men and There Will Be Blood offered darker visions of the West), in video games (Red Dead Redemption immerses players in the gritty life of cowboys and outlaws), and in contemporary literature, which often deconstructs the myth to uncover the human reality beneath it.

He also features in popular TV series like Yellowstone and its prequels 1883 and 1923, which transpose the rancher figure into both historic and present-day America. Each era reinvents the cowboy to reflect its own concerns: a symbol of rebellion in the 1950s (James Dean in a Stetson), of anti-establishment resistance during the hippie era (Sergio Leone’s ironic spaghetti Westerns), or today, a figure of diversity and genre-blending (as seen in today’s artists and designers).

More than 150 years after the era of the great ranches, the cowboy continues to roam—not only the plains, but also our collective imagination. He remains a fluid symbol, straddling authenticity and fantasy, allowing America to tell itself stories—its own stories—and see itself reflected in him. Free, resilient, courageous, and always ready to be reborn in new forms, the cowboy embodies a timeless part of the American soul.

That’s why, from the log cabin to the red carpet at the Grammys, he remains stitched into the national narrative of the United States—a figure sometimes realistic, sometimes dreamed, but absolutely inseparable from what we call Americana.

Sources

This article draws on a variety of sources, cross-referenced between archives, historical popularization articles, and cultural analyses. Andrew Fisher’s essay, published by the Bill of Rights Institute, provided insight into the cowboy’s daily life—work, movement, cattle drives—in connection with the economic expansion of the West. The Wikipedia pages dedicated to cowboys and cattle drives offered a complementary general and chronological framework. Contributions by Lakshmi Gandhi and David Lauterborn, published on History.com, enriched the historical approach by highlighting the Mexican heritage of the vaqueros, the role of former slaves after the Civil War, and the erasure of many cowboys from minority backgrounds.

The mythological dimension of the cowboy—between reality and legend—was explored through resources from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum and the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, particularly on the rise of Wild West Shows and the visual codification of the cowboy in media. The question of diversity, too often missing from traditional narratives, was addressed using the Black on the Range project developed by Rancho Los Cerritos. Finally, the contemporary aesthetic influence of the Black cowboy in fashion was analyzed through an article by Fast Company, shedding light on its cultural and visual reclamation in today’s creative spheres.

Follow us on Instagram

FAQ